In the summer of 1976, 26-year-old Raosaheb Kale entered the School of Life Sciences at New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University, alongside about 34 other incoming doctoral students. At the time, a committee of teachers at the school would review the students’ records and assign each to a PhD supervisor to mentor them through graduate school.

When the school posted the list of assignments, Kale scanned the piece of paper: Every single student, he said, had been matched with a supervisor, except for him.

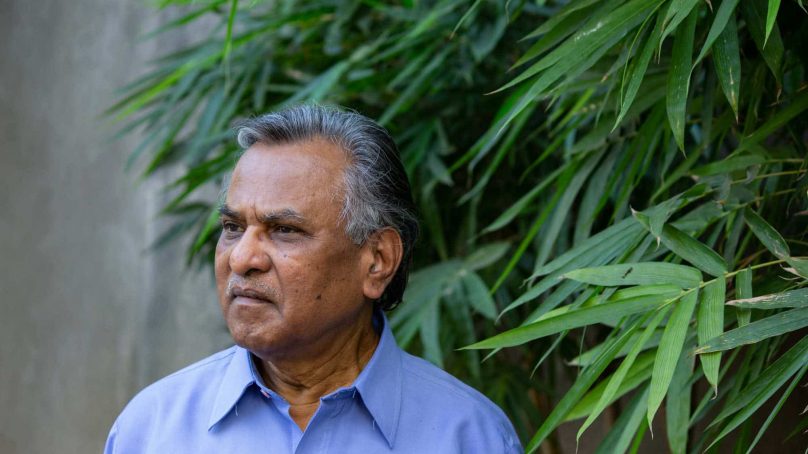

“Nobody wanted to take me,” recalled Kale, who is now 71, sitting on his apartment’s balcony in Pune, in western India.

Kale knew why his name was missing: In his class, he was the only one from the Dalit community – formerly known as the untouchables. The teachers didn’t want to supervise Dalits, Kale said, because they perceived that Dalits “won’t perform well.”

Historically, Dalits were considered so low that they fell outside the caste system, a rigid social hierarchy described in ancient Hindu legal texts. Brahmins (priests) occupied the top of the pyramid, followed by the Kshatriyas (warriors), Vaishyas (traders) and then Shudras (artisans) at the bottom.

Today, caste, which is defined by family of origin, remains an ever-present reality in Indian culture and functions somewhat similarly to race in America.

Growing up in the drought-prone Beed district of western India, Kale shared a mud-walled, tin-roofed house with his parents and four younger siblings. Like other Dalits, his parents were unable to own land and barred from entering temples.

In his village, Dalits were assigned various jobs such as sweeping streets, supplying firewood, delivering messages, and picking cotton. In return, they received grains, leftover food, or, on very rare occasions, one rupee for a day’s labour – well below a liveable wage.

When Raosaheb Kale, a member of the Dalit caste, entered graduate school in the 1970s, he was the only student the school did not match with a PhD supervisor.

“Nobody wanted to take me,” Kale said. In Indian culture today, caste, which is defined by family of origin, functions similarly to race in America. Visual: Ankur Paliwal for Undark

The village was peaceful as long as Dalits followed the Hindu caste hierarchy. “You know your limits,” Kale recalled. “The moment lower caste crosses the limit, ignorantly or otherwise,” anything can happen, he said. Once, when Kale was a kid, he recalled holding the hand of a higher-caste boy to cross a river in the village. A furore erupted. An older upper-caste person from the village warned parents of both boys that such close contact should never happen again.

Against staggering odds, Kale excelled in academic science. He fought his way through the upper-caste dominated School of Life Sciences, became its dean and received a prestigious award for his contributions to radiation and cancer biology research.

In 2014, he completed his tenure in one of the top academic posts – vice chancellor of a university – in India. But his story remains rare. In 2011, around 17 per cent of India’s population, which now totals over 1.3 billion people, were Dalits, who are officially referred to as “Scheduled Castes” in government records.

Caste discrimination is illegal, and India’s reservation policy – a form of affirmative action that has been around since 1950 – currently mandates that 15 per cent of students and staff at government research and education institutes, with some exceptions, come from the Dalit community.

But records obtained by Undark under India’s Right to Information Act from some of the country’s flagship scientific institutions, along with data from government reports and student groups, reveal a different picture.

At the elite Indian Institutes of Technology in Delhi, Mumbai, Kanpur, Kharagpur and Madras, the proportion of Dalit researchers admitted to doctoral programmes ranged from six per cent (at IIT Delhi) to 14 per cent (at IIT Kharagpur) in 2019, the most recent year obtained by Undark.

At the Indian Institute of Science, or IISc, in Bengaluru, 12 per cent of researchers admitted to doctoral programmes in 2020 were Dalits. And at the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research — a major government research institution – of the 33 laboratories that responded to Undark’s data requests, just 12 met the 15 percent threshold.

The numbers are even lower among senior academics. IIT Bombay, in Mumba and IIT Delhi had no Dalit professors at all in 2020 — compared with 324 and 218 professors, respectively, in the General Category, which includes upper-caste Hindus and some members of religious minorities, like Muslims.

In India, the term “professor” refers to senior-ranking positions and does not include assistant or associate professors.

IISc had two Dalit professors and 205 General Category professors in 2020. None of the department heads at IISc were Dalit last year. And five out of the seven science schools of Jawaharlal Nehru University did not have a single Dalit professor.

“You know your limits,” Kale recalled. “The moment lower caste crosses the limit, ignorantly or otherwise,” anything can happen, he said.

Similar disparities exist in other professions in India; Dalits face continued discrimination and violence from upper-caste people across the country. But researchers who study casteism in science say that even as Dalits have mobilised for their rights, they have encountered distinctive barriers in scientific institutions, which remain especially resistant to reservation policies and other reforms.

At a time of growing attention to inequities in global science, those barriers leave Dalits systematically underrepresented in the major research and academic institutes of the world’s largest democracy.

Undark sent repeated interview requests to the directors of IISc and five leading IITs. Only one responded, but declined to comment. In interviews, some upper-caste researchers said that finding qualified Dalit researchers can be difficult.

“When you’d sit in the interview board, you will find out yourself,” said Umesh Kulshrestha, the dean of Jawaharlal Nehru University’s School of Environmental Sciences, who is upper caste. Some Dalit candidates “can’t answer even easy questions,” he said, later adding that he has “some good quality Dalit researchers” in the school.

Several other upper-caste researchers simply denied that caste prejudice was common in Indian science, saying that they didn’t believe in caste.

But interviews with Dalit scientists and scholars show a different picture – one in which systematic discrimination, institutional barriers, and frequent humiliation make it difficult to thrive at every step of their training.

- A Nature magazine report