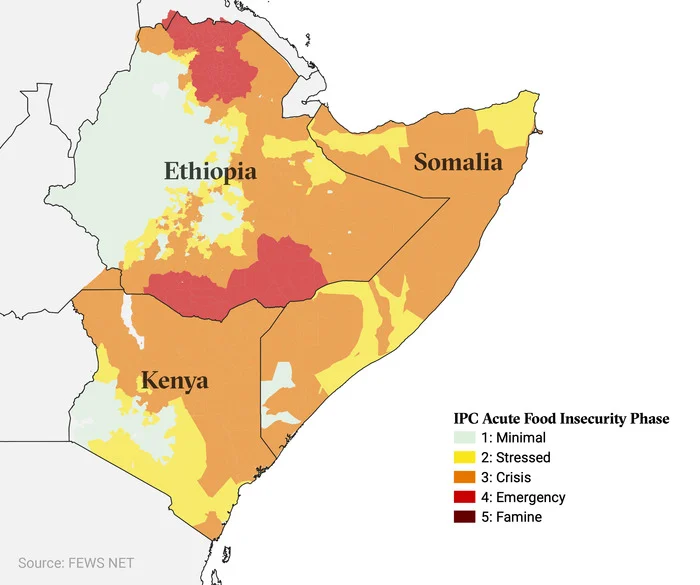

The current stretch of failed rains in the Horn of Africa has hit a region that had barely begun to recover from the 2016-2017 drought. With no pause to enable pasture and water points to regenerate, estimated 20 million people’s ability to cope has been stripped away.

In southern Ethiopia, more than 6.8 million people need aid. There have been at least 1.4 million livestock deaths – worth hundreds of millions of dollars – with almost 70 per cent of animals perishing in the Somali region alone. It’s not just a financial hit: Like Somalia, milk is the main source of nutrition for children. Again, malnutrition rates are alarming and rising.

The statistics aren’t much better in northern Kenya. More than three million people are short of food – an almost 50 per cent increase since August 2021. Over 1.5 million livestock have died, even while the government and aid agencies have trucked in water and provided emergency fodder and cash disbursements.

“We are now in a crisis response; in a couple of weeks, it will be a matter of life and death,” said Hussein Noor, with the aid agency Mercy Corps. “Markets [in northern Kenya] have crumbled, so traditional cash aid doesn’t work; drought relief now needs to be food relief.”

Food costs are surging across the region, partly a consequence of the record international prices for grains and the new impetus of the Ukraine war. That not only compounds the crisis for poor households, but also means already limited donor funding now buys even less.

“What’s clear is that the drought response is not getting even close to what’s needed,” said Taylor. With so many other emergencies – from Afghanistan to Ukraine – “donors are tapped out”. But it goes beyond money: “We also need leadership; we haven’t seen a donor step forward to own this crisis, to organise a regional pledging conference,” he added.

Drought obscures the politics that is also to blame for hunger. Somalia has been at war for almost three decades – a conflict that has left millions of people perpetually in need and with a weak and donor-dependent federal government, whose authority extends little beyond the capital, Mogadishu.

The jihadist group, al-Shabab, controls swathes of the countryside and enforces a strict isolation of rural communities. It distrusts mainstream Western aid agencies, especially the World Food Programme, which it accuses of undermining local farmers.

Counterterrorism legislation also blocks donor-funded relief organisations from working in insurgent territory. “Only the ICRC [International Committee of the Red Cross] and the Somali Red Crescent have access to areas under al-Shabab control,” explained Ahmed Abukar, director general of Somalia’s Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs.

Some small community-based NGOs are allowed in, but this is only at the discretion of individual al-Shabab commanders, and the amount of aid they can deliver is tiny.

Policy choices also play a role in the drought crisis in Kenya. Traditionally, the sparsely populated northeast has been politically marginalised. Although devolution has decentralised power, the legacy of that approach means markets and trade links remain weak.

That has a bearing on pastoralists who – learning the droughts’ lessons – are trying to shift from traditionally large, prestige-earning herds that are difficult to keep healthy, to more sustainable smaller holdings of better-fed animals, which have a higher market value.

Global warming almost guarantees that droughts in the Horn of Africa will become more frequent and severe. Before 1999, failed rains affected the region every five to six years, “but now it’s more like two to three years”, said Ahmed Ibrahim, southern Somalia representative for Save the Children.

“Pastoralists have always found ways to adapt,” noted Philip Thornton of the Nairobi-based International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI). “But in a situation where conditions are changing so rapidly, it gives them no time for trial and error, to find what works.”

Heat stress, disease, and the loss of biodiversity will affect humans and livestock alike – with animal productivity predicted to fall sharply. Competition between desperate pastoralists is likely to lead to increased conflict.

Somalia’s recurrent droughts have already forced hundreds of thousands of people to leave the land, squeezing into displacement camps on the periphery of urban centres. With no animals left, there’s little chance they’ll be able to resume their former lives.

In the town of Baidoa, in central Somalia, newly arrived people wait outside a displacement camp before being given space to build a makeshift shelter.

For Kurso in Luglo, it’s still a struggle to come to terms with her new-found destitution. “If I do go back, I don’t want to be a pastoralist,” she told The New Humanitarian.

But pastoralism need not be so hazardous. There’s growing evidence that drought action can be improved with the right measures. These include: the international community responding early to immediate needs; doubling down on interventions to build resilience to the next drought; and that investments now reduce the price tag of future emergencies.

“We need to build more durable solutions, to build capacity and institutions, or we are just scratching the surface,” Melaku Yirga, Mercy Corps’ director for Ethiopia, says.

“At the moment, we oscillate between drought and ‘normal’ responses; but we need to recognise that drought is actually the new normal.”

- The New Humanitarian report