For every illegal drug, there is a combination of emojis that dealers and consumers use to evade detection on social media and messaging platforms. Snowflakes, snowfall and snowmen symbolise cocaine. Love hearts, lightning bolts and pill capsules mean MDMA or molly. Brown hearts and dragons represent heroin. Grapes and baby bottles are the calling cards for codeine-containing cough syrup or lean. The humble maple leaf, meanwhile, is the universal symbol for all drugs.

The proliferation of open drug dealing on Instagram, Snapchat, and X – as well as on encrypted messaging platforms Telegram and WhatsApp – has transformed the fabric of illegal substance procurement, gradually making it more convenient and arguably safer, for consumers, who can receive packages in the mail without meeting people on street corners or going through the rigmarole of the dark web.

There is no reliable way to gauge drug trafficking on social media, but the European Union Drugs Agency acknowledged in its latest report on the drivers of European drug sales that purchases brokered through such platforms “appear to be gaining in prominence.”

Initial studies into drug sales on social media began to be published in 2012. Over the next decade, piecemeal studies began to reveal a notable portion of drug sales were being mediated by social platforms. In 2021, it was estimated some 20 per cent of drug purchases in Ireland were being arranged through social media.

In the US in 2018 and Spain in 2019, a tenth of young people who used drugs appear to have connected with dealers through the internet, with the large majority doing so through social media, according to one small study.

Some dealers these days are even brazen enough to boost their posts and pay for sponsored advertising. “Mushrooms and marijuana used to be hard to get and now they’re being marketed to me in beautiful packaging on Instagram,” says one 34-year-old in Austin, Texas. Dealers ran hundreds of paid advertisements on Meta platforms in 2024 to sell illegal opioids and what appeared to be cocaine and ecstasy pills, according to a report this year by the Tech Transparency Project, and federal prosecutors are investigating Meta over the issue.

“You’re seeing a more sophisticated commoditisation of the available marketplaces,” says Adam Winstock, a British consultant psychiatrist and addiction medicine specialist who is also the founder of the Global Drug Survey. The current drug-using younger generation are entirely used to getting everything online, he adds, reflecting the increasing integration of social media in people’s lives. “It’s convenient, [and] there’s less chance of violence.”

There are heightened concerns over the presence of super-strength opioids like fentanyl in drugs. But despite some contaminated pills having lethal effects on those who purchased them on the internet, Winstock says that drugs purchased through online networks are subject to “potentially better quality control” – with Telegram channels devoted to discussing the quality of drugs purveyed by certain dealers, and Amazon-style feedback sections within some vendors’ stores. “The question is where in the food chain that they’re cut,” Winstock says.

The menus provided by dealers through messaging apps and on social media are often lengthy and diverse, featuring prized varieties advertised for their purity and sold at significantly lower costs than equivalents available on the streets of London and New York.

However, there’s been no formal evaluation of online and street drug sales that can attest to the relative purity and safety of what’s sold in either place – and illegal drugs always come with a safety risk, regardless of where they are bought from.

Even while traditional drug transactions continue to dominate, the apparent rise in sales of drugs through social media has coincided with a steep increase in the average value of transactions on the dark web, amid a fall in the overall number of transactions, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime’s 2024 World Drug Report. To the UNODC, this suggests “an increase in wholesale activities” on the dark web – although this could also reflect consumers who buy smaller quantities shifting from the dark net to the clear net and encrypted messaging apps.

“End users seem to be buying their drugs on the dark web to a lesser extent than in previous years,” the UNODC said in its 2023 report. “Qualitative information provided by people who use social media suggests that the use of such media for drug purchasing purposes has been increasing, especially at the retail level.”

The shifting market trends also bring troubling developments. New and potentially more vulnerable population segments can be reached by exploitative drug dealers as they begin to sell on social platforms and the number of drug consumers in the US and around the world grows.

The US Drug Enforcement Administration has warned that because dealers are “no longer confined to street corners and the dark web,” social media users’ posts and inboxes can be peppered by dealers seeking to purvey these addictive and, when misused, harmful drugs. “Social media extends the reach of the Sinaloa and Jalisco cartels directly into drug users’ phones, with potentially fatal consequences,” the DEA said in its 2024 national drug threat assessment report, bemoaning that dealers are more difficult to apprehend online than the streets.

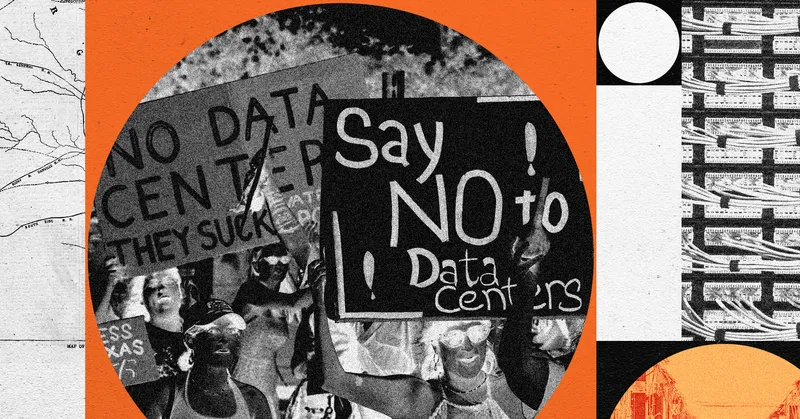

Social media companies are under growing pressure to eradicate drug dealing on their platforms, says Ashly Fuller, a PhD candidate at University College London researching the sale and advertisement of illegal drugs to young people on social media. Data released by social media companies shows that millions of pieces of drug-related content are already taken down every year.

Facebook and Instagram took action against 9.3 million pieces of drug-related content last year, while Snapchat says it did so in 241,227 cases in the second half of 2023. But these companies’ actions are sometimes indiscriminate. The accounts of organisations promoting drug harm reduction and social media personalities who post content about drugs and psychedelics, but who do not sell them, are being caught in the crossfire of efforts to get a grip on the issue.

- A Tell Wired report