Rising populism, fake news, and the ending of a global pandemic – the international challenges of almost 100 years ago uncannily echo the present, a unique archival project in Geneva reveals.

Archivists and historians are making a permanent digital copy of almost every document, letter, memo, photo and map from the doomed predecessor of the United Nations. The online League of Nations archives will be a rich resource for understanding the past, dealing with the troubled present, and shaping the future, according to project staffers.

“To have a better understanding of our world today, maybe we should look back sometimes,” said Pierre-Étienne Bourneuf, a historian working on the project. “The foundations of our international system were actually laid in 1919.”

The League was set up in 1920 as an attempt to manage international relations in the aftermath of World War I. Members included powerful European nations and a few independent countries in the Global South. It struggled to exert authority. Major powers boycotted or ignored it amidst worsening developments in the 1930s.

“We are facing today challenges that are very similar to what happened in the thirties.”

Its failure was epitomised for many by a 1936 speech by Emperor Haile Selassie of Abyssinia (modern Ethiopia) calling – fruitlessly – for protection from Italian Fascist invasion. The original speech, in parallel Amharic and French versions, is on exhibit at the UN’s Palais des Nations complex in Geneva – and will be an iconic entry in the new digital archive.

The League of Nations was abandoned in 1939 at the outbreak of a second European war it failed to prevent. It was dissolved in 1946, and its assets – including thousands of boxed papers and files – transferred to its successor: the UN. The documents – until now only available to researchers at the UN Geneva library – will soon be viewable to everyone.

The project team says there’s a lot to learn. “We are facing today challenges that are very similar to what happened in the thirties,” Bourneuf said. Asked for examples, he noted: the fallout of the “Spanish Flu”; rising authoritarianism; and the League adopting a resolution against false news, and also addressing terrorism, slavery, and the status of women.

The League of Nations archives are noted as a unique record in the history of international relations, recognised in Unesco’s world heritage listings. The records, held at the Palais des Nations, are being scanned and catalogued in a five-year, $25 million project.

The hard copies are being preserved in the same filing system as originally handed over, but in new boxes that better protect the fragile papers. Project manager Colin Wells said the unique venture is funded by a private Geneva-based foundation that wishes to remain anonymous.

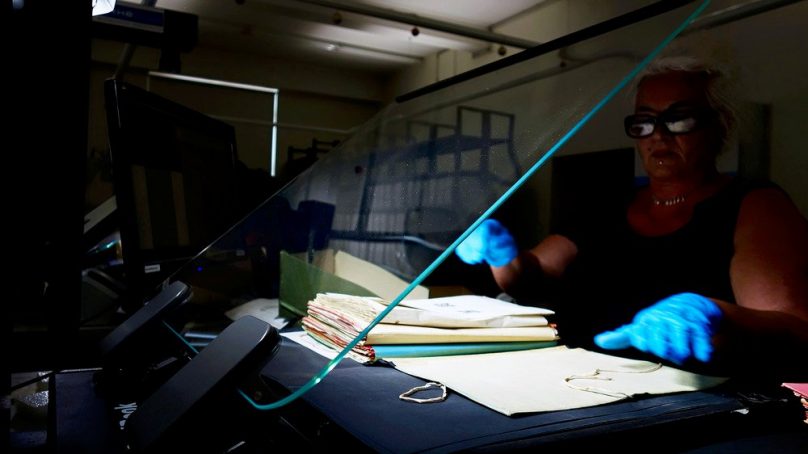

Digitising the archives, containing thousands of folders and loose-leaf files, requires a painstaking process of preparing the physical papers, cataloguing, scanning, and checking. Archivists iron out creases, repair torn pages with specialist adhesives, and even clean off dirt with special erasers.

Once the documents have been prepared, a team of contractors scans each page – using dedicated camera rigs – into a heavy-duty digital storage system. A quality control process catches any blurred or illegible images.

Optical character recognition software converts typewritten or printed text into computer-readable files in French and English, but can’t decipher handwriting or other languages. An experimental project with the University of Lausanne is attempting to apply automated face recognition to the photo archive.

The result will be a web-based library of about 15 million pages and other items freely available online to the public, historians, and researchers – on everything from the administration of Cameroon to the invasion of Abyssinia. The collection covers public health concerns (including leprosy control and the tail end of the Spanish flu pandemic).

It includes passports pioneered by Norwegian scientist and humanitarian Fridtjof Nansen that the League issued to stateless people. It also has records related to various territories – colonies seized by the French and British allies from Germany and the Ottoman Empire – governed under “mandates” formalised at the League.

The collection also captures the minutiae of the operations of the institution – expense claims for sending telegrams, for example, or, more intriguingly, the disciplinary records of badly behaved bureaucrats that were once classified as secret. One document detail how a diplomat got into trouble with the Swiss authorities for riding his bicycle too fast.

The photographic archive appears – unsurprisingly – dominated by men with moustaches having meetings. Bourneuf said the history of the League too has generally been written by white men. But the online project gives “a possibility to democratise access to the archives”, he added, saying that inclusivity in looking at the past is important for the future of multilateralism.

“We need to hear different voices,” Bourneuf said. “New historians – that could not come to Geneva – will be able to provide a new perspective, a new historiography… and to provide another voice that will maybe complement, maybe contest what we think is the truth.”

The League’s demise, project manager Wells said, suggests a cautionary tale for the UN: “if there’s no will of its member states to act and to enforce international law, the structure isn’t going to be able to hold.”

- The New Humanitarian report