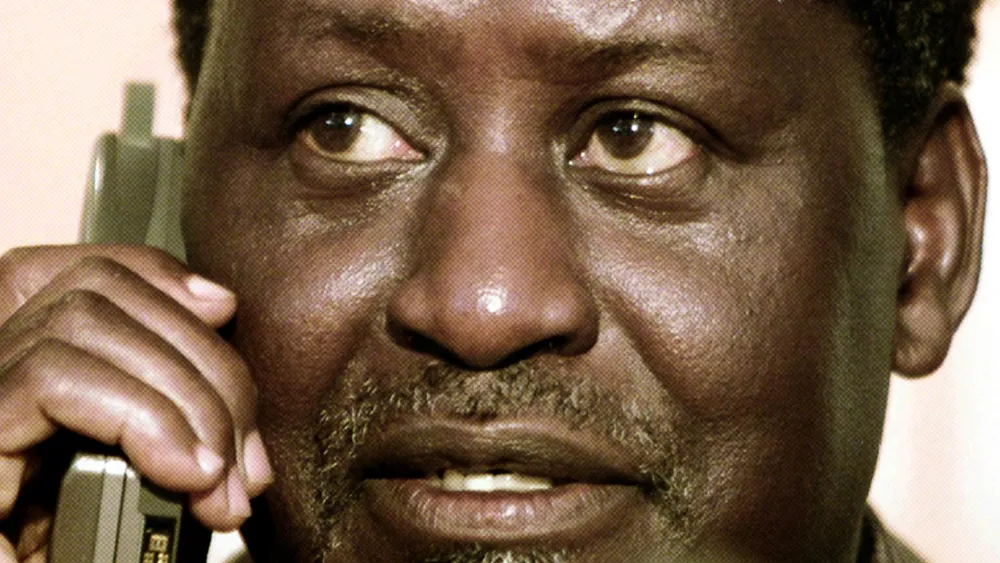

Raila Odinga, the legendary Kenyan politician who passed away last week, has long been feted as a champion of democracy and good governance, not just in Kenya, but across the entire continent.

In a career spanning decades, he built a formidable reputation as a campaigner and mobiliser for accountability and electoral reform, and is celebrated as the conscience of a nation.

“In the end, Raila Odinga’s greatest legacy may be that he made politics matter, that he convinced millions, for decades, that the ballot could be a moral instrument,” wrote Nyambura Mundia in a widely cited piece published in The EastAfrican. But that may be overstating things a bit. Raila did not make Kenyans care about democracy. He made them care about power.

Like many of his generation, Raila had inherited a political philosophy that viewed power as the precondition for justice. In his book, Not Yet Uhuru, Raila’s father, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, relates how – during a stand-off between the two main African political parties at the 1962 Lancaster House negotiations over Kenya’s independence constitution – Jomo Kenyatta argued for compromise: “We had to reach a settlement. If we failed, government would be snatched from our hands. If we brought no government back with us, the people would regard it as an arch failure”.

And then the kicker: “We might be forced to accept a constitution we did not want, but once we had the government, we could change the constitution”.

Thus the pre-eminence of power was established. The rules of the game could wait. The point was to seize the board. That logic became the foundational premise of Kenyan politics. KANU got the power. And it did change the constitution – not to empower the people, but to entrench itself. It justified the silencing of dissent, the centralisation of authority, and the rewriting of the constitution to suit those in charge.

Tom Mboya, one of the brightest stars of the independence era, once argued that Kenya did not need an opposition – dissent, he said, would only slow development. Dissent was inefficiency; unity under power was progress.

The generation of politicians who came after entrenched and modernised this doctrine. In the 1980s and 1990s, the push for a return to multiparty politics was spearheaded by the rallying call, “Moi Must Go!” – a reference to the dictatorship of Daniel arap Moi. It was about creating a path to power, not necessarily building a mechanism for controlling how it was exercised, although it did later result in a clamour for a new constitution.

However, even that was constantly held hostage to the desire for power, resulting in a number of false starts and a quarter-century wait for Kenyans. Fifty years after Kenyatta had declared that, “if we brought no government back with us, the people would regard it as an arch failure,” Mwai Kibaki, with Raila’s backing, brought the government, but, like Kenyatta and his acolytes, proceeded to attempt to subvert the push for a better constitution.

Raila, in particular, was responsible for turning what had been a strategy of the elite into a mass mobilisation tool: He convinced millions that justice lived on the other side of victory. Although he stood with Kenyans against the corruption and oppression of successive regimes, his remedy – exemplified in his record five failed attempts to secure the presidency – was a version of Kwame Nkrumah’s famous adage, “Seek ye first the political kingdom, and all things shall be added unto you.”

Thus the ballot was more than a mechanism of representation; it was a weapon of deliverance. Power was the tool to right historical wrongs and democracy merely the path to it, not an end in itself. It is a creed that survives today. Kenyan politics remains plural in form but authoritarian in soul. Elections are not civic exercises but wars of conquest. And once in power, every regime speaks the language of democracy while thinking in the logic of siege.

Democracy is tolerated only for the promise of delivering power, not for the much more important function of containing it.

The 2007-2008 post-election violence revealed this mind-set at its most catastrophic. That year’s election was not a disagreement over policy; it was a zero-sum fight between Raila and Kibaki for control. After the country burned, with well over 1,200 people killed and more than 600,000 displaced, the political elite emerged from the ashes with a power-sharing deal, not a reckoning.

This reveals Kenya’s tragedy: Accountability is rarely more than a slogan. Elites invoke justice only when it serves their ascent. They do not seek to build institutions to restrain power but rather movements to capture it.

Raila’s genius was to make this feel moral to a large section of the populace. But by predicating justice on the attainment of power, he did more than make defeat intolerable. In such a world, there is no role for the opposition in governance; its sole objective becomes to unseat the incumbent, not to regulate the exercise of public power.

More than anything else, and largely to the exclusion of everything else, politics continues to revolve around fights over arrangements for the next election – the near constant demand for “minimum reforms”. As a result, Kenyans have become fluent in the politics of power but illiterate in governance.

Small wonder, then, that many of them now admire “benevolent autocracies” – Singapore, Rwanda, China – that promise order and prosperity without the mess of democracy. We praise efficiency and discipline over freedom and debate. Democracy is tolerated only for the promise of delivering power, not for the much more important function of containing it.

This is not uniquely Kenyan. Across the world, democracy is being hollowed out by the same logic. From Trump’s America to Modi’s India and Orban’s Hungary, populists insist that liberal democracy has grown weak and obstructive and that justice demands decisive control. Even defenders of democracy are trapped in the paradox.

In a recent conversation between US public commentators Ta-Nehisi Coates and Ezra Klein, the latter pushed for an accommodation with voters with authoritarian and supremacist leanings. To preserve democracy and human rights, he argued, the left must win power. And to do so, it must be willing to undermine democracy and human rights by aligning with those who reject them. Power first; principles later. It is Jaramogi’s old credo, updated for the 21st century.

What lessons for Gen Z?

Kenya’s experience offers a warning. Power does not purify politics; it consumes it. Every generation of liberators has campaigned against tyranny only to inherit its instruments. We have built the rituals of democracy – elections, constitutions, commissions – but rarely its ethics. Power changes hands, yet politics never changes character.

Throughout the 1990s, Kenyans showed that the opposite approach – prioritising change over power – was effective. In that decade, citizens successfully rolled back the state without capturing it. They did so by building and empowering institutions outside government: civil society organisations, churches, mosques, the media, and grassroots movements that could stand up to the regime. This coalition of actors set the reform agenda that eventually allowed Kenyans, in 2002, while still under Moi’s rule, to sing they were “unbwogable” or “indomitable” and to shortly thereafter end KANU’s four-decade monopoly on power.

The Gen Z movement that has brought young Kenyans into the streets of major towns and cities over the last two years has yet again shown that a different kind of politics is possible, one grounded in governance rather than the pursuit of power.

Yet, even as they did so, they were seduced by the appeal of power, and in the elections that removed KANU from power they also decapitated the very movement that had enabled change, voting many civil society and religious leaders into parliament. Within a year, the new government had reverted to the old ways of corruption and oppression, and it took another eight years – and a near-descent into civil war – to force a new constitution on the reluctant elites.

It is all the more tragic that this lesson appears to have been forgotten and history is repeating itself.

The Gen Z movement that has brought young Kenyans into the streets of major towns and cities over the last two years has yet again shown that a different kind of politics is possible, one grounded in governance rather than the pursuit of power. These young protesters have, to a large extent, resisted the familiar mechanisms of co-option by the state, from Raila-style “handshakes” to elite bargains disguised as reconciliation.

For a time, before the state turned to violence and abductions, they focused on policies rather than personalities, using social media to convene massive online forums where tens of thousands dissected tax policy and land law. It was, briefly, a glimpse of a politics of consent rather than coercion.

But that fragile distinction is under strain. The movement’s rallying cries – Wantam (the call to deny President William Ruto a second term) and Ruto Must Go – suggest a slide back into the old grammar of power. They risk repeating their elders’ mistake: confusing the capture of power with the creation of change.

To be fair, Raila’s faith in power was not cynical. He genuinely believed that with power he could right Kenya’s wrongs. And he may well have, had he gotten the chance. But therein lies the problem. Without constraining power, one is reduced to hoping for benevolence but having no way of guaranteeing it. And the history of dictatorships suggests you are more likely to end up with a Pol Pot than a Lee Kuan Yew.

If Kenya has anything to teach the world, it is that power cannot build the politics meant to restrain it. Democracy cannot simply be a road to victory; it must be the terrain on which we all stand, win or lose.

- A Tell Mdia report / By Patrick Gathara – Senior Editor for Inclusive Storytelling/ Republished with the permission of THz New Humanitarian