The rain was pouring as my tuk-tuk (rickshaw) made its way along the Mogadishu-Afgoye highway. Informal settlements line both sides of the 30-kilometre corridor that links the capital to the agricultural lands of the Lower Shabelle – a corridor that for decades has been a place of refuge for people fleeing war and drought.

Aside from the security checkpoints, there is little government presence along the newly asphalted road as you pass row upon row of cramped tents and metal shacks – made all the grimmer by the rain.

Most international aid groups don’t send their foreign staff here: The corridor marks the beginning of contested territory, where the insurgent group al-Shabaab wields influence. Last year, an aid worker from Türkiye was killed on the same road.

Families who live here call this neglected real estate home. That includes the Kahiye household, who settled in the Sinka Dheer informal settlement, 15 kilometres from Mogadishu, more than a decade ago after warring clan militia drove them off their land in the village of Ceel-Warego, near the coastal town of Marka.

Mohamed Kahiye’s farmland provided a livelihood for his family. “But after repeated attacks I could no longer stay,” he says. Militia from a rival clan had ransacked his village and pillaged his crops. “Homes were being set ablaze. There were a lot of killings,” Kahiye said.

Historically, militia from Somalia’s more powerful clans have targeted the marginalised farming communities in the fertile Shabelle Valley. Moving to Mogadishu and the periphery – where aid groups were operating and there was some stability – seemed the only viable option.

“I settled with my family in Sinka Dheer: At first, I thought it would be temporary, but now we’re in our 12th year,” said Kahiye, 46. “I can’t go home because the danger we initially fled still exists, but the city life [of Mogadishu] is also out of reach [financially]. So we’re forced to make do with what we have.”

A decade ago, there were more than 400,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) living along the corridor. But while many households have moved closer to Mogadishu to try and find work, more people still continue to arrive and settle along the road.

Sinka Dheer is a maze of metal shacks, mosques, restaurants, stores, and pharmacies. But it is also an administrative no man’s land: It doesn’t fall under the jurisdiction of the Mogadishu municipality and neither is it recognised by the neighbouring South-West State. That means there are no public services reaching the residents here.

“It’s like we’re stateless,” said Kahiye. “The government [in Mogadishu] is not here and neither is South-West. We can’t return home, so we are left to deal with these circumstances on our own.”

The weakness of state institutions, after years of war, limits the federal government and Mogadishu municipality’s administrative reach. Al-Shabaab and its two-decade-old insurgency is another challenge. The jihadist group vies with the authorities for control and legitimacy in areas outside the main towns – including the countryside beyond Afgoye.

“The displaced people are stuck in the middle – and then you have clans also claiming some areas,” said Aweis Mohamed, the research director for the Somali Public Agenda (SPA), a Mogadishu-based think tank. “Every step you take you’ll see a clan claiming it. This makes the prospects for these people getting local services and help even more difficult.”

“Nearly everyone here has been displaced from different parts of the country, but we all have one thing in common – no one can return home.”

It takes 20 minutes to reach Sinka Dheer from Mogadishu – depending on the length of the queues of cars, buses, and tuk-tuks at the checkpoints. It’s a busy trading centre, where those who have managed to make enough money from roadside vending graduate to brick-built shops.

Sitting in a restaurant was Abdikadir Omar Adow, 27, a relatively new face to the area. He fled fighting in his home region of Hiran during late 2022. Government troops and clan militia allies – backed by US and Turkish air support – had launched an offensive against al-Shabaab, with fighting continuing into the first quarter of 2023.

A lifetime ago, before arriving in Sinka Dheer, Adow was a pastoralist herding livestock near the town of Boco, on the banks of the Shabelle River. But as the conflict intensified, he fled southwards to Mogadishu, until “things calmed down” he imagined. But they never did, and parts of Hiran have switched hands on numerous occasions.

“Nearly everyone here has been displaced from different parts of the country, but we all have one thing in common – no one can return home,” said Adow.

After decades of upheaval, there are more than four million IDPs across Somalia, roughly a quarter of the population. Most have settled in Mogadishu, giving the city one of the fastest urbanisation rates in the world. Like Adow, few people contemplate returning, so home becomes wherever you can build it.

The challenge for the authorities is how to integrate this uprooted population: to provide land, public services and political representation – rights that will change the demographics of cities like Mogadishu.

Adow believes that if Sinka Dheer was administered as a formal settlement by either Mogadishu or South-West State, its residents would have a political voice to demand greater inclusion.

“If Sinka Dheer is recognised as a town or district, we would get a mayor, local council, and more,” he said. “There are health clinics, restaurants, and mosques here, but yet everyone (non-IDP) view us as if we don’t exist.”

Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed, director of the Somali Humanitarian Organisation (SHO), a community development NGO, noted that extending essential services – from health to schools – “can have a life-changing impact” on urban IDPs.

Yet providing the land and housing that would help settlements become formalised represents a financial and political hurdle. Addressing those barriers starts with understanding what a viable housing integration policy for IDPs would look like, and then figuring out how to implement it.

“This can be done on a grassroots basis with community elders, members of the IDP community, and local government agreeing on fair land distributions that align with current realities,” said Mohamed of SHO.

Yet those “realities” are far from insignificant. They include highly charged issues around land ownership, land pricing, and tenure rights for IDPs who – lacking political and economic clout – are vulnerable to eviction by landowners.

“Land prices have skyrocketed in the area between Mogadishu and Afgoye,” said Mohamed of SPA. “Similarly, claims of ownership by clans and limited government capabilities to implement policies or decrees in this area make it difficult to integrate IDPs within the local community.”

Clan dynamics are a particular complication. Mogadishu is dominated by powerful major clans, especially the Hawiye. The majority of IDPs, however, are from marginalised so-called minority groups, including farm-based Bantu people.

“Incorporating these settlements within Mogadishu could change the power balance,” explained an urban development expert, who asked for anonymity given the sensitivity of clan issues. “This could affect the electoral map as well as the business and economic dynamics in Banadir [greater Mogadishu].”

To overcome the “deep levels of mistrust” within Somali society, he added, an administratively strong state is needed to “reconcile the populace to pave way for integration”.

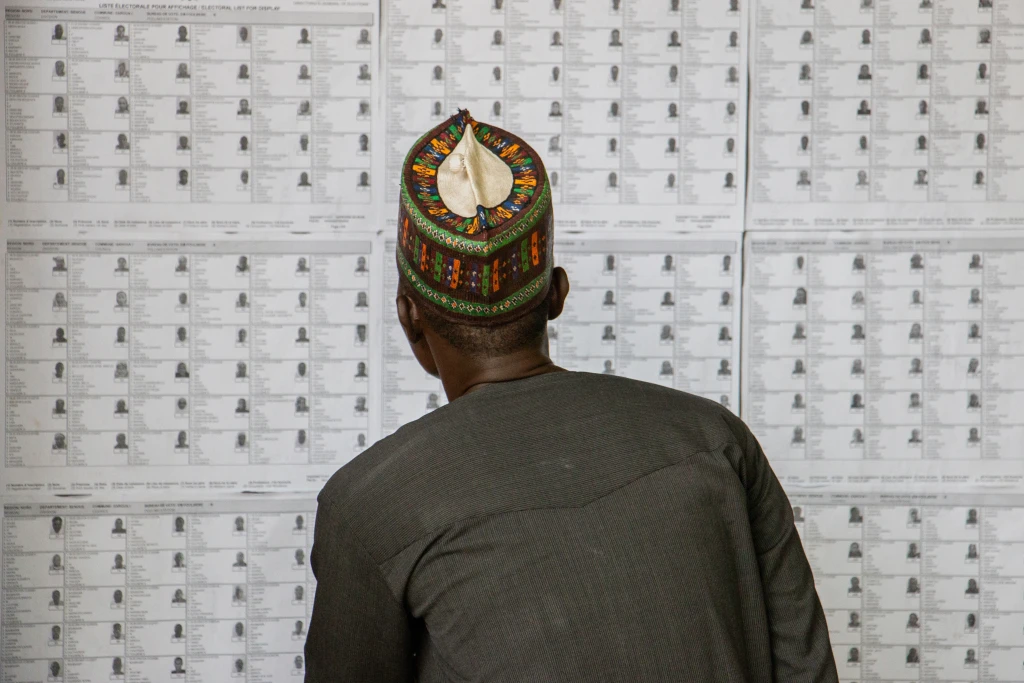

However, a degree of integration has happened already. In May 2024, the federal government recognised three new districts that were incorporated into Mogadishu. One of these was Garasbaley, a former informal settlement on the Mogadishu-Afgoye corridor.

There was a similar boundary shift in 2012 that incorporated Kahda – another informal settlement – into Banadir. Today, it has grown into a sprawling district with newly built homes, shops, and public services, including a police station and garbage collection.

“Things won’t change overnight, but recognising some of these informal settlements is a beginning,” said the urban expert.

- A Tell Media report