Visionary colonialism is not a widely accepted or established concept, but it may refer to the idea that colonialism can be a vehicle for progress or modernisation. In this article I am advancing the idea that British colonialism in East Africa was visionary colonialism with reference to its innovation of the concepts of cooperation, integration and federation, although it was prone with injustices in Kenya since 1888; Uganda since 1894; and Tanganyika since 1920.

When our East African rulers talk of East African cooperation, federation and integration, they seem to give the impression that the three ideas started with them. But the truth is that the three ideas were introduced by the British colonialists during the more than 70 years they conquered, occupied, grabbed land and forcibly ruled the three the East African countries as one empire connected to the British feudal arrangement.

To this end, the idea of an East African federation uniting Kenya, Uganda and Tanganyika was politically pursued during the colonial times in East Africa. The British colonialists were probably influenced by the truism that their former territories in North America had federated to form the United States of America. They wanted a similar model for East Africa to create The East African Federation, which would result in effective cooperation between the three countries of the region.

The colonialists wanted political and economic integration and cooperation within a federation; not social integration. There was a lot of resistance to federation, particularly by Buganda in Uganda. It was not federation and integration to empower the countries but to facilitate more effective domination and exploitation of the region.

To effectively govern the empire, the colonialists introduced what they characterised as the East African High Commission (EAHC) on January 1, 1948 to provide common services in Uganda, Kenya and Tanganyika. Although colonialism was a vehicle for enhanced domination and exploitation, the British rulers emphasised effective management and delivery of services as civilization. The services included posts and telecommunications, customs, taxation, meteorological services and harbours. It was a body corporate capable of owning property and engaging in legal actions.

The EAHC existed until 1961 when it was abolished and replaced by the East African Common Services Organisation (EACSO), which the newly politically independent countries of Uganda, Kenya and Tanganyika inherited from the colonialists.

EACSO continued to exist even after Tanganyika, Uganda and Kenya obtained their political independence in 1961, 1962 and 1963 respectively. It ceased to exist when the newly independent countries created the East African Community (EAC) in 1967.

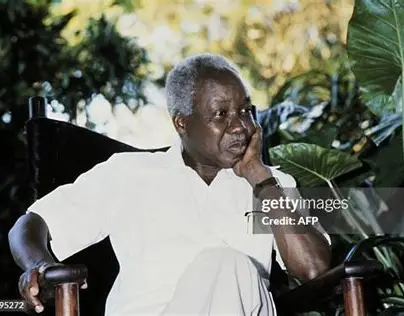

EAC was an intergovernmental entity, which focused time, energy and money on economic integration and cooperation; not political integration, which has been resisted. It was the result of the treaty for East African Cooperation signed by Presidents Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, Kambarage Nyerere of Tanganyika and Apollo Milton Obote of Uganda.

EAC preserved and perpetuated the common services conceived under EACSO, but included railways, Airways, posts and telecommunications, research institutions such as East African Marine Fisheries Research Organisation (EAMFRO), East African Freshwater Research Organisation (EAMFRO) and East African Trypnosomiasis Research Organisation (EATRO). The East African Treaty also created a University Students Exchange Programme, Joint Examinations Council and an East African Parliament.

The federal motive did not completely dissipate when the independence fever caught the East African countries. This motive expressed itself most in the development of higher education. Makerere University college was established by the colonialists in 1922 and became linked to the University of London became the centre of higher education in East Africa. It played a critical role in socially transforming the countries of East Africa through producing advanced manpower for the three colonial entities. The exceptionally intelligent were sent to universities in Great Britain.

For a long time there was no other centre of higher education in East Africa. However in Kenya, the first university – Egerton – was established in 1939 by Lord Maurice Egerton as a whites-only farm school. .Egerton was a British national who settled in Kenya in the 1920s. It eventually became an agricultural university. Royal Technical College, Nairobi, was established in May 24 1964. University College, Dar-Salaam was established on October 25, 1961. Like Makerere University College, Royal College, Nairobi, and University College, Dar -es-Salaam were affiliated to the University of London.

Makerere University College started to grant degrees in 1949 but remained affiliated to the University of London until 1963, when the governors of the newly independent countries of Tanganyika and Uganda and the still colonially governed Kenya agreed on 29 June 1963 to establish the Federal University of East Africa. The first chancellor of the University of East Africa was Julius Kambarage Nyerere. He was installed at the inauguration of the university.

The new university immediately became affiliated to the University of London. From that time, all degrees obtained by students of Makerere University College, Royal University College, Nairobi and University College, Dar-es-Salaam were granted by the Federal University of East Africa 1963-1970. In 1970 the University of East Africa was dissolved.

All the three constituent universities of the now defunct Federal University of East Africa became independent universities that granted degrees separately from each other: University of Nairobi, University of Dar-es-Salaam and Makerere University. They also became independent of the University of London.

President Julius Kambarage Nyerere became the chancellor of the University of Dar-es-Salaam, President Jomo Kenyatta became the chancellor of the University of Nairobi, and Apollo Milton Obote became the chancellor of Makerere University. However, they had a student exchange programme conceived under the East African Community.

In 1972 I, together with people like Muhimbura, Lutalo Rugumayo, Ngobi, Bagambiire, Ms Jjuko, Ms Rusoke, Ms Namakula, Chemisto, Balirwa, Mufumba, Gwaira, Olwitingol, Mukubwa, and Rwetangabo – joined the University of Dar-es-Salaam under that programme.

Therefore, for the East African countries becoming politically independent was one thing. And becoming academically and intellectually independent was another. For a long time, the University of London babysat the academic and intellectual growth and development of the earlier universities in East Africa except Egerton University. Was this visionary colonialism? May be, but we should always remember no foreigner helps you without helping himself or herself first and all the time.

For God and my country.

- A Tell report / By Oweyegha-Afunaduula / Environmental Historian and Conservationist Centre for Critical Thinking and Alternative Analysis (CCTAA), Seeta, Mukono, Uganda.

About the Centre for Critical Thinking and Alternative Analysis (CCTAA)

The CCTAA was innovated by Hyuha Mukwanason, Oweyegha-Afunaduula and Mahir Balunywa in 2019 to the rising decline in the capacity of graduates in Uganda and beyond to engage in critical thinking and reason coherently besides excellence in academics and academic production. The three scholars were convinced that after academic achievement the world outside the ivory tower needed graduates that can think critically and reason coherently towards making society and the environment better for human gratification. They reasoned between themselves and reached the conclusion that disciplinary education did not only narrow the thinking and reasoning of those exposed to it but restricted the opportunity to excel in critical thinking and reasoning, which are the ultimate aim of education. They were dismayed by the truism that the products of disciplinary education find it difficult to tick outside the boundaries of their disciplines; that when they provide solutions to problems that do not recognise the artificial boundaries between knowledges, their solutions become the new problems. They decided that the answer was a new and different medium of learning and innovating, which they characterised as “The Centre for Critical Thinking and Alternative Analysis” (CCTAA)