Cancer risk surged 23 per cent in people who received the Covid-19 vaccine, according to a peer-reviewed study published in EXCLI Journal in July 2025.

The risk of breast cancer jumped 54 per cent and bladder cancer rose 62 per cent within 180 days of the first vaccination, the study showed.

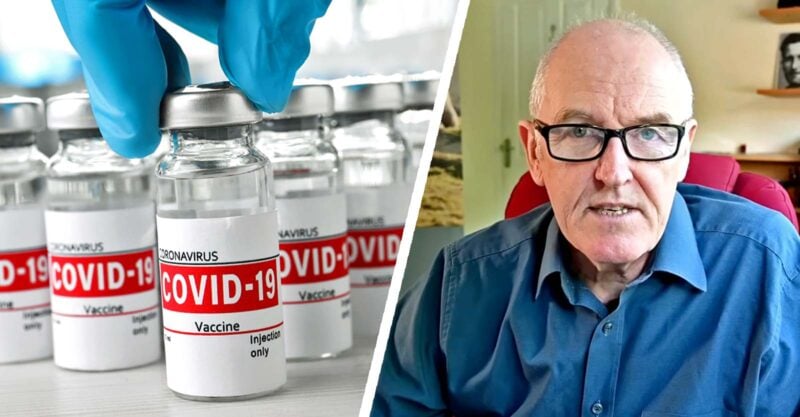

“This is real data and quite concerning,” medical commentator John Campbell, said on his YouTube show as he broke down the results.

The study was the first to uncover statistically significant evidence of increased cancer risk following Covid-19 vaccination.

Researchers examined the long-term relationship between SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations and cancer hospitalisations in a population-wide cohort of nearly 300,000 residents of Pescara province, Italy.

Residents aged 11 and older were followed from June 2021 through December 2023 using official National Health System data.

The statistical models were adjusted for age, sex, comorbidities, prior cancer and prior SARS-CoV-2 infection, making it the most comprehensive follow-up to date on cancer diagnoses following Covid-19 vaccination.

The risk of cancer diagnosis was 23 per cent higher for people vaccinated with one or more doses within 180 days of the first vaccine, versus the unvaccinated, the study found. Among the 296,015 people studied, 3,134 were diagnosed with cancer.

“Even with this relatively small sample size,” Campbell said, there is “only one chance in a thousand that this result arose by chance.”

People receiving at least three doses of the Covid-19 vaccine had a 9 per cent increased risk of cancer diagnosis within 180 days of the third vaccination, compared to the unvaccinated.

Two factors contribute to the drop in increased risk with more vaccine doses, Campbell said.

“One is that those people that were predisposed to get cancers basically had already developed it” before the 180-day post-third-dose deadline was reached, Campbell said. “So perhaps the 23 per cent increase in cancers at six months means that people that are going to get cancer … may get it early.”

Secondly, cancer follow-up requires decades for adequate analysis, he said.

There were no long-term Covid-19 vaccine studies, and “that was the whole problem,” Campbell said. “They vaccinated the control groups in very short order … so the whole thing was a complete debacle.”

“We won’t know the answer … for the next 10, 20 years … as more people are diagnosed with cancer,” he said.

Breast, bladder and colorectal cancers showed the highest, statistically significant increases in vaccinated patients compared to unvaccinated.

The risk of breast cancer increased 54 per cent and bladder cancer rose 62 per cent in people with at least one dose of the Covid-19 vaccine, 180 days after they received the shot. Colorectal cancer was up 34 per cent.

In people with at least three doses of the Covid-19 vaccine, at 180 days after the third dose, the risk of breast cancer was up 36 per cent and bladder cancer was up 43 per cent.

The risk of colorectal cancer rose 14 per cent, but this increase was not considered statistically significant due to the small sample size in the study. Uterine and ovarian cancers also showed increases following both one and three doses, although the numbers were not statistically significant.

Campbell explained, “It looks like there’s a genuine increase, but when you take into account the fact that [3,134] people were admitted with cancers, when you broke that down by cancer types, sometimes the numbers weren’t sufficient to give a statistically significant result.”

However, if the study were on a larger scale, “my suspicion is that these would be, I’m afraid, highly, highly significant,” he said.

In addition to analysing cancer risk, the study assessed the risk of all-cause mortality associated with Covid-19 vaccination status.

Results showed vaccinated people had a lower likelihood of all-cause death throughout the study.

“This is almost certainly attributable to what we call the healthy vaccinee effect,” Campbell said. “We were told, manipulated, lied, whatever you want to call it, that this vaccine was good for our health. So, people with an interest in health tended to get vaccinated.”

The study’s authors said the same healthy vaccinee bias that makes vaccines look like they reduce deaths could also underestimate cancer risks. They wrote: “The healthy vaccinee bias, similarly to how it likely leads to an overestimation of vaccine effectiveness against all-cause death, could also lead to an underestimation of the potential negative impact of vaccination on hospitalization due to cancer. Indeed, the healthier lifestyle that is typically associated with vaccination may reduce the risk of lifestyle-associated carcinomas.”

Campbell agreed with the authors. Vaccines caused or were associated with more cancers than they were able to identify, he suggested.

Certain biological factors indicate an association between the Covid-19 vaccines and cancer, according to Campbell, who said: “Ongoing production of spike protein will cause inflammation. Ongoing inflammation is associated with cancer. Autoimmune attacking of the tissues will cause chronic inflammation. …

“DNA contamination … there certainly is a great theoretical risk of cancer, largely by inhibiting tumour suppressor genes. Frameshifting … you end up with rogue proteins. … Rogue proteins, inflammation, any mutation, of course, is a cancer. I mean, our cancer starts as a mutation. So lots of plausible mechanisms there.”

Evidence pointing to the dangers of the Covid-19 vaccines is growing, yet governments refuse to release detailed information on vaccinations versus health incidents, Campbell said, calling that failing “quite outrageous.”

The lack of data suggests “a cover-up, and it’s not acceptable,” he said. “But sadly, this is the current period of time we are in.”

- A Tell Media report / By Jill Erzen, associate editor for The Defender