I was born in the southeast of Haiti, the eldest of a small family that only included my mother and my sister. We were raised in Port-au-Prince, and from early on my childhood was marked by frequent hospital visits due to my severe asthma.

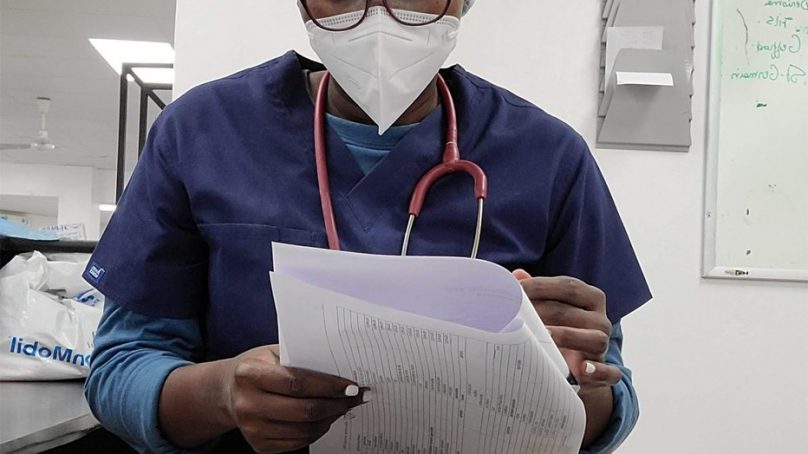

What stayed with me the most of my numerous visits to the emergency services was the empathy and kindness of the medical staff. Their compassion inspired me from a young age to become a doctor so that I could one day provide the same care and hope to others.

The financial burden of my studies was heavy on my mom. But I had the fortune to have people help sponsor my education. The support I received from others along my journey motivated me to give back: going to medical school was not just a personal ambition but a calling to serve my community.

Success often feels like a path we carve for ourselves, a road paved with hard work, sacrifices, and dreams. I was walking along that path. After seven gruelling years in medical school, I graduated, completed my mandatory year of social service, and entered a residency in Emergency Medicine at the University Hospital of Mirebalais (HUM), a city of the Centre department, northeast of Port-au-Prince.

The specialty quickly became my passion. The chaotic intensity of emergency care fuelled me. I found meaning in learning to manage critically ill patients, in reviving lives that teetered on the edge. The beeping of a heart monitor after resuscitation, the relief on a family’s face, the knowledge that I was getting the skills to make a difference in people’s lives – this was my purpose.

But outside the hospital, my country was crumbling. Political instability worsened, gang violence spread like wildfire and safety became an illusion. Despite it all, I held onto my work while adapting to the insecurity, limiting my mobility and going to Port-au-Prince only when really needed. Residency was demanding, but it kept me grounded.

On my weekends off, I embraced what little normalcy remained – exploring the Centre department’s breath-taking waterfalls and rivers, dancing to the sweet rhythm of Konpa and other social dances, and immersing myself in the beauty that still exists amid the chaos.

Yet, the violence kept closing in. My family and friends urged me to leave Haiti, warning me that staying was too much of a risk for health workers who are increasingly targeted. But I refused; I was determined to contribute to my country in any way I could.

Everything changed during a nightshift in September 2023. I was beginning my second year of residency. It was a Monday – I remember being full of energy, ready for my 24-hour shift, rotating through the surgical service.

Throughout the day, I received messages from friends, both in Haiti and abroad, warning me: Rumours were spreading that gangs were planning to attack Mirebalais. I reassured them, half-joking: “Don’t worry about me – I’m safe. I’m on shift, inside the hospital. I’m not even near the exit door.”

At around 1:40am, however, something felt different. Suddenly, a senior resident ordered me to go to my room. Confused – we still had patients needing urgent care – I asked why. A colleague quietly told me there were reports of gang presence near the hospital.

On my way to the resident quarters, another colleague told me: “Go to your room. Pack a backpack – a pair of jeans, two t-shirts, your important papers. Be ready, just in case you need to leave quickly.”

Leave? I thought. Leave to go where? It’s the middle of the night, I am in the middle of my shift, inside a hospital.

Still, I obeyed. My roommate was asleep. I was going to take my backpack to fill it with my things, but I looked at my sleeping roommate as if to confirm that I was in the hospital, that I was safe. It all felt surreal. I put the backpack, still empty, back where it was. I didn’t need it, I thought. Then, I got into bed in my uniform and set my phone’s volume high in case I was called back to work.

I must have dozed off for a few minutes until the heavy, terrifying sound of gunfire woke me up. My roommate and I looked at each other wide-eyed before she quickly went to check the door. “I locked it,” I whispered.

Before we could exchange another word, the gunfire grew louder, closer – the sound of military-grade automatic weapons firing non-stop. We instinctively threw ourselves onto the floor. Then came a pounding knock on our door. We held our breath, frozen. We could hear men’s voices, footsteps. Was it the gangs?

Suddenly, a woman’s voice broke through: “It’s me, please open the door.” It was a new resident – her very first night in the hospital. She had been alone in her room and was too afraid to stay by herself. We let her in. The three of us spent the rest of the night on the ground, shaking, praying, and listening to the chaos outside.

That night dozens of gang members surrounded the hospital and entered the courtyard, firing shots at the building from outside. Miraculously, no one was hurt or killed. Usually, some of the patients’ parents would have been sleeping in the courtyard, but when the staff heard that a gang was in the vicinity, they had sheltered them inside. The bullets had left windows broken and damaged several parts of the hospital.

In the following hours, when the quiet came back, it was obvious that Mirebalais was compromised. We needed to leave.

The hospital leadership did their best to organise a proper evacuation but everything was delayed, and the fear kept rising. Some staff who had cars began leaving on their own, taking a few others with them. Watching them go made the rest of us feel abandoned and hopeless. Eventually, we decided to start walking, hoping to find some kind of public transportation.

Even though the evacuation was spontaneous and driven more by instinct than planning, the hospital leadership made sure we would be welcomed in other different hospitals of the Zanmi Lasante network – Haiti’s main non-governmental health provider, which the Mirebalais University Hospital is part of.

When we reached the gate, we realised we were not alone. Residents of Mirebalais were also leaving on foot with their essential belongings, many of them carrying babies in their arms, desperate, not knowing where to head.

We managed to find a few motorcycle drivers willing to take us, for payment. We split into smaller groups, and I rode with the new resident who had hidden in my room towards a hospital in a small town on the outskirts of the city.

Shots were still being fired, I don’t know if by gangs or self-defence groups. Our driver did his best to dodge them and get us out of there fast. Along the way, the scene was heart-breaking: families walking barefoot, carrying children, with only the hope of finding safety.

Afterwards, my colleagues decided to go wherever they felt safest – back to their hometowns, to Cap-Haïtien (the main city in the north) or to Hinche. I chose to go between the two, to my sister’s home in Pignon.

Today around the world, healthcare workers are increasingly on the front lines not just of illness, but of war, conflict, and societal breakdown – and the consequences reach far beyond the walls of any hospital.

In Haiti, the crisis is both political and criminal. Kidnappings of healthcare workers have become tragically common. A 2024 survey in Port-au-Prince showed that 44 per cent of healthcare professionals had a colleague kidnapped in the previous two years.

The surge of gangs has led to widespread road blockages, effectively cutting off entire communities from essential medical services. Public hospitals have closed, and private healthcare remains out of reach for most due to prohibitive costs and accessibility issues. This has resulted in a health crisis where emergency, primary, and chronic care services are either unavailable or inaccessible for the majority of the population.

Ambulances are routinely targeted by gangs. Several hospitals were directly attacked and even burned down. Reaching a hospital can mean risking your life.

I know of pregnant women in labour, writhing in pain who were unable to reach a hospital to deliver their baby; of mothers watching helplessly as their children’s sicknesses worsened, with no access to medical care; of an elderly man who suffered a heart attack, but the emergency room was out of reach. There are car accident victims, asthma patients gasping for air, people with chronic illnesses needing urgent medication – all left to fend for themselves; gunshot victims lying bleeding, with no hospital to save them.

And when patients do manage to reach facilities, they are often met with long waits or are turned away altogether.

The night the hospital where I worked was attacked, there were more than 350 patients, many in critical condition. The hospital’s neonatal intensive care unit housing helpless new-borns was also shot at, leaving several incubators damaged and endangering vulnerable babies.

In Mirebalais, I took care of many patients with very complicated conditions. The hospital served primarily central Haiti, but as it is particularly well-equipped and very affordable, people came from all over the country to seek care. Even there, however, resources were limited.

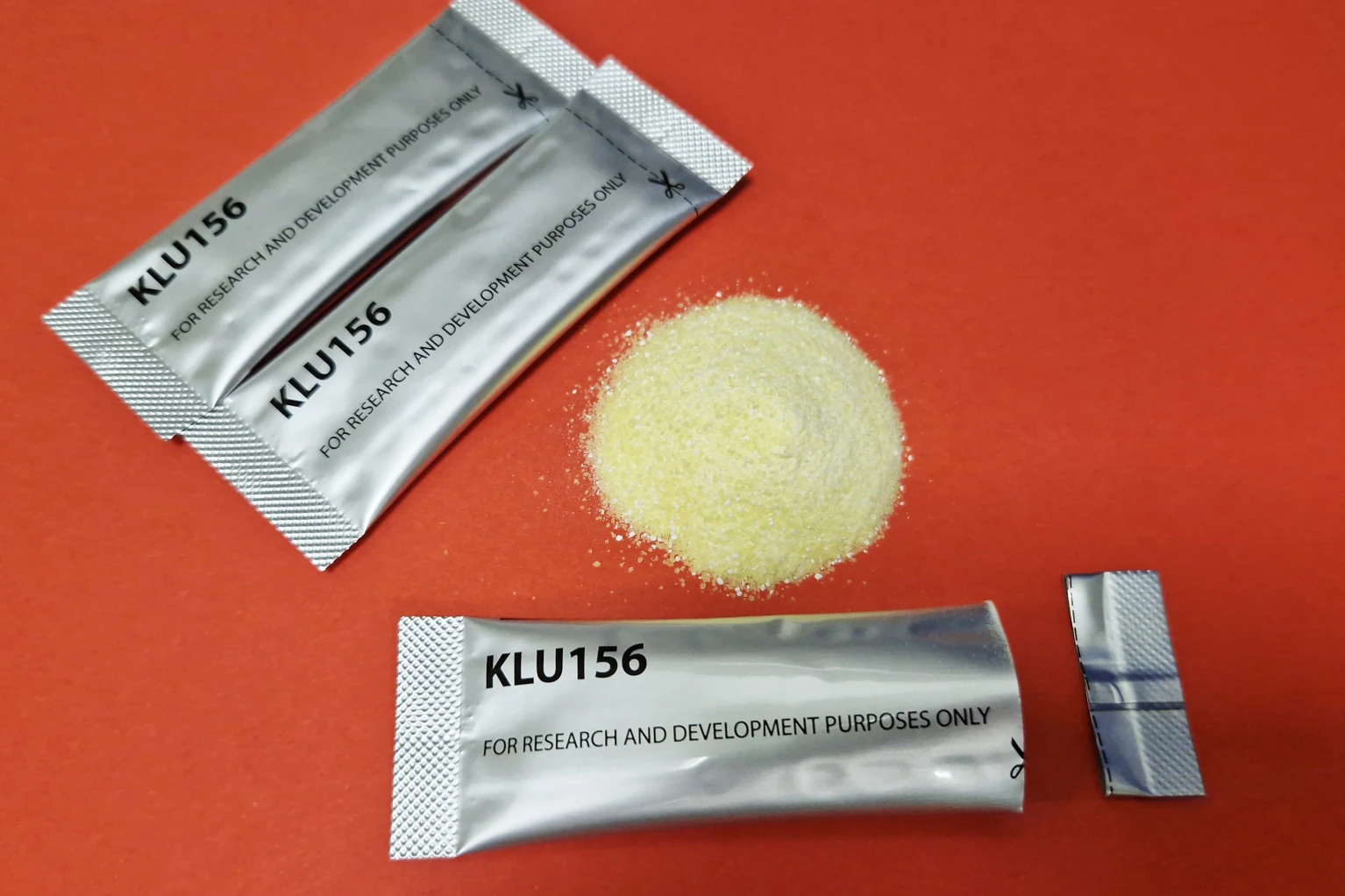

Being a doctor in Haiti is very challenging. We often don’t have the tests, treatments or equipment that we need and have to improvise. Often, we know exactly what should be done for a patient, but the necessary supplies aren’t available. We have seen patients die from treatable health issues. At other times, the insecurity on the roads has made it impossible to transfer the patients or they arrived too late to be helped.

It happened to a friend of mine. She lived in Port-au-Prince and had felt a small lump in her breast two years earlier, but doctors had told her it was nothing serious. After she gave birth to her first child, the lump grew bigger and painful. By April 2023, she was not well, did some tests, and sent me the results. They were not good.

I told her to come to the Mirebalais University Hospital, but when she arrived she already had signs of advanced cancer. She also developed cirrhosis, generalised swelling, and hepatic encephalopathy. There was little we could offer her at that stage.

I saw my friend decline in front of me. On her final night, I stayed close to her, struggling with the reality. After my shift, I returned to my room exhausted and heavy-hearted. A few minutes later, two co-workers knocked on my door. Before they spoke, I knew. I ran back to the emergency room, where she was lying under a white sheet. Her husband stood nearby, devastated.

As they placed her body in a bag to send to the morgue, I broke down in front of colleagues, patients, and staff. It was unbearable – not only because I lost a friend, but because her death was preventable. She was only 28 years old.

My friend’s story is just one example of how fragile our healthcare system is. A system where preventable diseases become death sentences, where delays, costs and limited access to timely care steal lives every single day. It’s a reminder of the cost of a weak health system and of the urgent need for change.

This is not just a national crisis; it is a humanitarian emergency. The world cannot look away. Political leaders, human rights organisations, and the international community should engage in immediate intervention by providing humanitarian aid, supporting healthcare systems, and promoting conflict resolution. We need policies and sanctions that will protect hospitals, ensure safe access to medical care, and uphold the basic human right to health.

Families often see the Mirebalais University Hospital as their last hope, and that is a heavy weight to carry. Even with all the effort and sacrifice, there were moments when we could not do enough.

These moments stay with you. There is pride when you succeed against the odds but also guilt when you know what should have been done but couldn’t be. Many doctors in Haiti go home asking themselves if they are truly useful despite doing everything they can. We keep going because every life saved reminds us why we are there, and why our work matters.

But the circumstances have been forcing many health workers to abandon their posts, including me.

Leaving Haiti was a difficult decision, one I didn’t want to make. But the night of the gang attack forced me to reconsider. It was the hardest decision of my life: I had to leave my country, abandon my career, my dreams, and the community I had vowed to help.

I had never wanted to go despite the situation. I felt attached to my work and my community and I kept reassuring my family, telling them: “I live in a hospital, and it’s not in Port-au-Prince, so I’m okay.”

But when the gangs attacked Mirebalais, my mother insisted that I had to go and this time it felt less like a suggestion and more like an order. And I too, in those endless hours huddled on the floor, understood that nowhere was truly safe anymore in Haiti. I could no longer find excuses; my sense of safety had collapsed.

With a heavy heart, on November 3, 2023, I left Haiti for the United States — a country I had only travelled to previously for vacations. And just like that, my world collapsed.

I was consumed by anger, grief, and helplessness. I had lost everything, my career, my purpose, my place in residency. Every day, I struggled with the same haunting question: What now? The weight of depression crept in, and I found myself crying every night, mourning the life I had been forced to leave behind.

In Florida, where I live now, I can’t work as a doctor because I don’t have a licence to practice in the United States and have had to settle for a job as a medical assistant.

I am not alone in this. Many others like me — dedicated professionals, hopeful students, and hardworking Haitian citizens — have been uprooted by Haiti’s ongoing crisis. We are left in limbo, unable to practise our professions, struggling to rebuild from nothing, and battling the silent war of mental health.

This crisis is not just about politics or violence. It is about the human cost for the patients and their caregivers. It is also about doctors, teachers, engineers, and dreamers whose lives have been derailed. It is about a nation haemorrhaging its brightest minds, not because they want to leave, but because they have no choice.

- A Tell Media report / Republished with the permission of The New Humanitarian