Higher education institutions are increasingly being held accountable for maintaining quality in their activities by governments, industry, students and the community as a whole (Amal Said, et al (2020).

Besides, in light of the current rapid changes and developments nowadays, especially the explosion of knowledge and the technological transformation as a result of globalisation, the quality of education has become a must, with the emergence and spread of accreditation units and the demand to ensure the quality in the educational system at various stages. Therefore, the process of “measuring and evaluating the quality” is an important process, not only for the educational institution itself, but also equally for those who make educational politics and all parties interested in the educational process (Djouhari, et al, 2024).

Douglas C. Bennett, cited by Djouhari, classifies the approaches to measuring quality into six categories, summarised as the value-added approach, which focuses on measuring outputs, results, inputs, reputation, expert evaluation, self-reports, process input and participation rate (Youssef Djamal El-Din, 2012 cited by Djouhari, et al, 2024).

Value-added approach is also called the transformation approach, where value added means the improvement that occurs to students in their “abilities, knowledge, and skills” as a result of the education they obtained at a particular university or college.

There is the comprehensive approach, which attempts to overcome the partial nature and limited outlook that characterize other approaches, such as (the approach to measuring quality in terms of inputs, outputs and processes, according to expert opinions, etc.), which are the approaches that led to highlighting the necessity of a comprehensive treatment.

There is also the standards and indicators approach, a measurement and evaluation method, which relies heavily on quantitative indicators to judge the quality of the institution, such as the number of academic activities, the size of the library, the number of enrolled students and the results of course tests, in addition to looking at the awards the institution has received. Or by looking at the characteristics of the students, such as the quality of the programmes offered to them, the number of those holding a doctorate degree, or by looking at the research publishers belonging to this institution.

Some scholars believe that the quality of the student is related to the quality of the department; so they look at the results achieved by the students, and some of them look at the quality (Djouhari, et al, 2024).

Virtually every university in Africa in particular and the world in general has quality assurance bodies, which should ensure that the academic, administrative and financial conditions prevailing in the university are compatible with the requirements of applying comprehensive quality management, at the level of the current education philosophy and objectives, the structures and patterns of university education, the performance of faculty members, the tools of the educational process, the system of graduate studies and scientific research, the financial capabilities, and financing of university education that is based solely on funding. It is quality that evaluators of universities focus on to compare universities.

Their academic politics may lower the quality. It is worse if university leadership is a matter of national politics aimed at controlling whatever goes on in the university.

Nguyen and Ta (2017) believe that accreditation influences most of the university’s management activities, including programmes, teaching activities, lecturers, supporting staff, learners and facilities. They argue that the influence of accreditation contributes significantly to enhancing the university’s quality of teaching, learning, research and management.

They recommend improvement in the use of accreditation. On the other hand, Quyen (2019) sees both Quality Assurance and Accreditation as a mechanism for accountability in terms of quality.

Quality means that it is a system consisting of (inputs, processes, and outputs), and also includes a set of intellectual philosophies and administrative processes used to achieve the goals and the targeted competencies by raising the level of quality of the performance of professors, lecturers and students alike, and the continuous improvement of the institution.

Abdine (2004), cited by Djouhari, et al (2024), has defined quality as:

- Quality is conformity with specifications

- Quality is freedom from defects (conformity with purpose)

- Quality is achieving customer satisfaction

- Total Quality Management is a philosophy of continuous improvement.

There are 1,274 officially recognised higher-education institutions in Africa, according to uniRank 2024. This represents a portion of the 14,013 globally recognised institutions. There are also 97 African universities that are ranked in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings.

In 2025, there are approximately 1,258 universities in Africa. This number includes both public and private institutions. Specifically, there are 802 public universities and 456 private universities.

Despite efforts to improve quality of higher education in Uganda in particular and Africa in general the quality of education and research seems to be declining.

Kimeze (2024), citing Prof. Umar Kakumba, Deputy Vice-Chancellor of Makerere University, Uganda, in charge of academics, highlighted that the institution’s academic performance has been declining over the years, partly due to escalating under-staffing issues.

Way back in 2002 I was interviewed by Richard M. Kavuma and Alex B. Atuhaire of defunct The Monitor and I said that Makerere University was 35 years behind. They made my statement a headline of their article ‘Makerere University is 35 years behind’ in The Monitor of 19 September 2002. This then means Makerere University has been dropping behind for decades.

I read in the Daily Monitor of July 8 2025 that Makerere University has been ranked 41 in Africa tying with 31 other universities on the continent. Besides, Times Higher Education, a UK-based organisation that ranks universities globally, also bundled Makerere University between positions 1201 and 1500 globally in 2025.

In 2023 Times Higher Education ranked Makerere 5th in Africa South of the Sahara while in 2024, it fell to 8th position. The drop from 8th to 31 is a meteoric one. The fact that 31 universities, including Makerere, have been bundled together in the same position of 41 indicates that higher education in Africa is in crisis and the reasons might be universally the same. One thing is true: virtually all the universities in Africa are manifesting as if they are still in the 20th century, heavily stuck in the disciplinary ways of teaching, learning and researching.

Although the Daily Monitor (Draku, 2025) reports decline of Makerere University, the university’s Vice-Chancellor, Barnabas Nawangwe, is cited saying that the university remains competitive and a magnet of international conferences. In other words, despite the fact that Makerere University is integral to the global higher education system, the VC does not believe that the reputable Higher Education Times is reporting correctly on Makerere University.

We must still ask, “Why has Makerere University, for long known as the Harvard of Africa, undergone such a meteoric drop? Wasn’t the university future-ready?”

JEPA (2025), in its article “A Fall from Grace? Unravelling of Makerere University,” mentions the following as the reasons why Makerere University has fallen from grace: Bottom-Heavy Administration, Research Pitfalls. Requisition of Funds and Suboptimal Facilities. JEPA concluded thus:

“Makerere Decline is emblematic of broader administrative challenge in Uganda’s higher education. The University’s once sterling reputation has been clipped away by bureaucratic inefficiencies, research stagnation, financial overhauls, and infrastructural decay……Makerere’s revitalisation does not seem to be an impossible feat. With the right reforms, the institution can rise again, reclaiming its place as the beacon of excellence. However, the question remains: will it act in time, or will it become yet another relic of unfulfilled potential?”

It is surprising that JEPA does not mention the possible impact of a leadership crisis in Makerere University, but instead delves into “broader administrative challenge”.

It is often said that behind every problem is the problem of leadership. A university such as Makerere University requires a leadership that is not oriented too much towards the powers that be and that concentrates on academic and intellectual production, emphasising the development of the academic and intellectual potentials of both its academic staff and students.

Besides, the leadership must be motivating. Motivational leadership is the ability of a leader to inspire, encourage, and drive individuals or teams toward achieving goals by fostering a positive work environment, setting clear objectives, and promoting growth and engagement. It’s about inspiring passion and commitment, not just directing tasks. The leadership must not be backward looking and must be fully aware and understand where higher education is going.

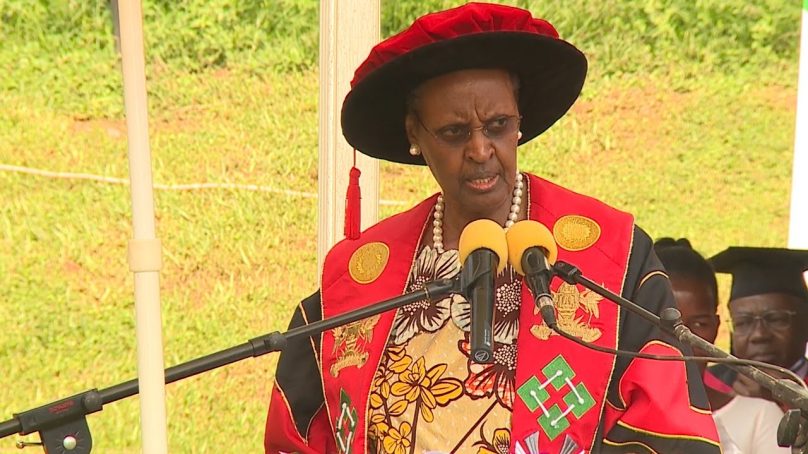

Makerere University is now squarely in the hands of the National Resistance Party (NRM); the Minister of Education is the wife of the NRM Supremo and President of Uganda, Tibuhaburwa Museveni; the Chancellor of the university, Dr Crispus Kiyonga, a long-term NRM cadre, a former minister and a former ambassador to China and Uganda Patriotic Movement (UPM) co-founder; the chairperson of the university council is Lorna Magara, a family friend and close confidant of the first lady and a sister to Allen Kagina; the chairperson of the Makerere University appointments board, which recruits and promotes academic staff, is Edwin Karugire, a son-in-law of President Tibuhaburwa Museveni.

It is likely the leadership of the ministry of education and Makerere University is not so much oriented towards ensuring that the university improves its academic and intellectual status by liberating it from excessive political control of its educational, academic, intellectual, recruitment and promotions processes in the university of the closely-knit family of the president. In essence, Makerere University is encircled by the president’s family – nuclear and extended

The current politically-oriented leadership of Makerere is not aware of the fact that interdisciplinarity, crossdisciplinarity, transdisciplinarity and extradisciplinarity are growing movements within academia globally. It seems to be satisfied leading a university buried in the past, superimposing disciplinarity and multidisciplinarity on a society that should be benefitting from integrative and integrating academic and intellectual processes.

While multidisciplinary scholarship isn’t intended to replace traditional approaches to teaching and research, “it absolutely is becoming increasingly important in academic scholarship (Palm cited by Pierce, 2022) in Makerere University and other universities worldwide at the expense of interdisciplinarity, crossdisciplinarity, transdisciplinarity and extradisciplinarity.

The recently published Amanya-Mushega Uganda Education Policy Review Commission Report 2025 completely ignores higher education, narrowly focusing on primary and secondary education and failed to rethink education for survival in a complex 21st century with its complex (or wicked) problems such as environmental conservation and climate change.

In one article ‘Treatise on Interconnecting Humanities, Arts, Social Science and Natural Science for Environmental Conservation – Uganda’s Case’ I laboured to show that complex problems such as environmental conservation can only be meaningfully and effectively addressed if education at our universities develop curricula that interconnect the broad fields of humanities, arts, social science and natural science.

In ‘Treatise on Alternative Universities: The Case of Centre for Critical Thinking and Alternative Analysis, Uganda’ I advocated a shift from disciplinary or multidisciplinary universities to more diversity-loving universities that emphasise critical thinking, critical reasoning and are welcoming to alternative analyses that are not disciplinary or multidisciplinary.

In ‘The Fate and Future of Public Intellectuals in Uganda’I stated that we need public intellectuals more today than yesterday, yet they are an endangered species. The aim should be to curtail the influence of think-tanks, consultancies and thought leaders, and to diversify the ideas industry and make the market place of ideas more enriching and dynamic.

In ‘Linking Academic Ageism, Intellectual Death and Decline of Public Intellectualism: Uganda in Perspective’ I showed that these three vices in our universities can be addressed to improve the academic, intellectual and research environment by making new policies that all disciplinarity, multidisciplinarity, crossdisciplinarity, transdisciplinarity and extradisciplinarity to coexist on compass, thereby creating a sea of alternative scholars and learners.

In another article ‘Knowledge Systems, Knowledge Workers and the Graduates from Our Universities in Uganda’, I have surmised that the soft spot for multidisciplinarity is not so much to improve the quality and performance of universities but to exclude other integrating knowledge systems from the university campuses.

Unfortunately, the Amanya Mushega Uganda Education Policy Review Commission (2022-2025) evaded these issues altogether, thereby leaving Uganda in the 20th century or superimposing 20th Century Uganda onto 21st century Uganda. Its policy solutions can only complicate our current education situation and make our complex problems even more complex.

Addressing complex real-world global challenges requires integrating academic work in universities and research centres. In order to do so, the research agenda has to shift towards transdisciplinary, interdisciplinary, crossdisciplinary and extradisciplinary co-construction of knowledge with academics and stakeholders in society (e.g., Oweyegha-Afunaduula, 2025).

New institutional arrangements and processes are needed but are insufficiently studied and implemented. Global South–South collaborations in interdisciplinary approaches are also crucial for successful evolution of academic responses (e.g. Bursztyn and Purushothaman, 2022). A university such as Makerere University should be at the centre of these changes and integral to them.

Instead, the leaders of Makerere University, both academic and administrative, continue to praise disciplinary and multidisciplinary scholarship (which is glorified disciplinary scholarship).

With alternative universities and alternative knowledge systems (Table 1), we are assured of alternative scholars and alternative graduates (Oweyegha-Afunaduula, 2025). Apart from multiple scholarships or scholars from different knowledge systems, we are assured of multiple literacies and a more diverse academia -more integrated, more dynamic, more productive and less monotonous.

Public intellectualism will be resuscitated on the university campuses and by extension in the entire Uganda society. The fear syndrome and conspiracy of silence, which bog university campuses will begin to be a thing of the past. We must be part of the age of new and different knowledge production and work to build new institutions that promote it to usher in new scholarship and a new graduate that is more independent-minded, more interactive, fear-free and knowledge-loving.

Right now the scholars and their students are under fear and a cloud of conspiracy of silence as the country suffers decay and collapse in every sector of the economy. Public intellectualism has been squeezed out of the university and from the public space outside it.

Table 1. The Knowledge Systems of the World, Scholars and Graduates, 2025

___________________________________________________________________

Knowledge System Type of Scholar Type of Graduates

Extradisciplinary knowledge System Extradisciplinary Extradisciplinary

Transdisciplinary knowledge system Transdisciplinary Transdisciplinary

Interdisciplinary knowledge system Interdisciplinary Interdisciplinary

Crossdisciplinary knowledge system Crossdisciplinary Crossdisciplinary

Multidisciplinary knowledge system Multidisciplinary Multidisciplinary

Disciplinary knowledge system Disciplinary Disciplinary _____________________________________________________________________

Taiwo Oluwadare, 2019citing Prof Aderemi Raji-Oyelade wrote:

“What does it mean to be literate in the age of (the new media) of multiple scholarships and multiple literacies? Without doubt, the new understanding of literacy in the new age is such that it invites multiple definitions, for literacy itself is a plural activity. “Specialisations are necessary; specialisations are industrial inventions of the Malthusian imagination. But at its worst example, specialisations breed the indiscipline of mutually exclusive disciplines. “…in this century, it is those who are capable of crossing the boundaries of the disciplines who will make the difference; it is those who possess the ability of disciplinary transgressions who can interact beyond the borders of their own specialisations; those who have privilege horizontal collaborations (across the planks or branches of the disciplines. “The character of cross-disciplinary practice is that one discipline illuminates the other in a concentric, mutually functional way that intellectual literacy is achieved across and within the disciplines.” “The promotion of scientific inventions without artistic/humanistic interventions is a movement towards mechanistic chaos, what can be imagined as progressive backwardness. Scientific/technological advancement without (the) ethical consideration of things runs the risk of foisting a generation of Frankensteins on the society.

For God and my country.

- A Tell report / By Oweyegha-Afunaduula / Environmental Historian and Conservationist Centre for Critical Thinking and Alternative Analysis (CCTAA), Seeta, Mukono, Uganda.

About the Centre for Critical Thinking and Alternative Analysis (CCTAA)

The CCTAA was innovated by Hyuha Mukwanason, Oweyegha-Afunaduula and Mahir Balunywa in 2019 to the rising decline in the capacity of graduates in Uganda and beyond to engage in critical thinking and reason coherently besides excellence in academics and academic production. The three scholars were convinced that after academic achievement the world outside the ivory tower needed graduates that can think critically and reason coherently towards making society and the environment better for human gratification. They reasoned between themselves and reached the conclusion that disciplinary education did not only narrow the thinking and reasoning of those exposed to it but restricted the opportunity to excel in critical thinking and reasoning, which are the ultimate aim of education. They were dismayed by the truism that the products of disciplinary education find it difficult to tick outside the boundaries of their disciplines; that when they provide solutions to problems that do not recognise the artificial boundaries between knowledges, their solutions become the new problems. They decided that the answer was a new and different medium of learning and innovating, which they characterised as “The Centre for Critical Thinking and Alternative Analysis” (CCTAA).