In a June report on Gaza, Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) system’s Famine Review Committee wrote that increases in aid were one reason the famine they had predicted in March likely didn’t happen.

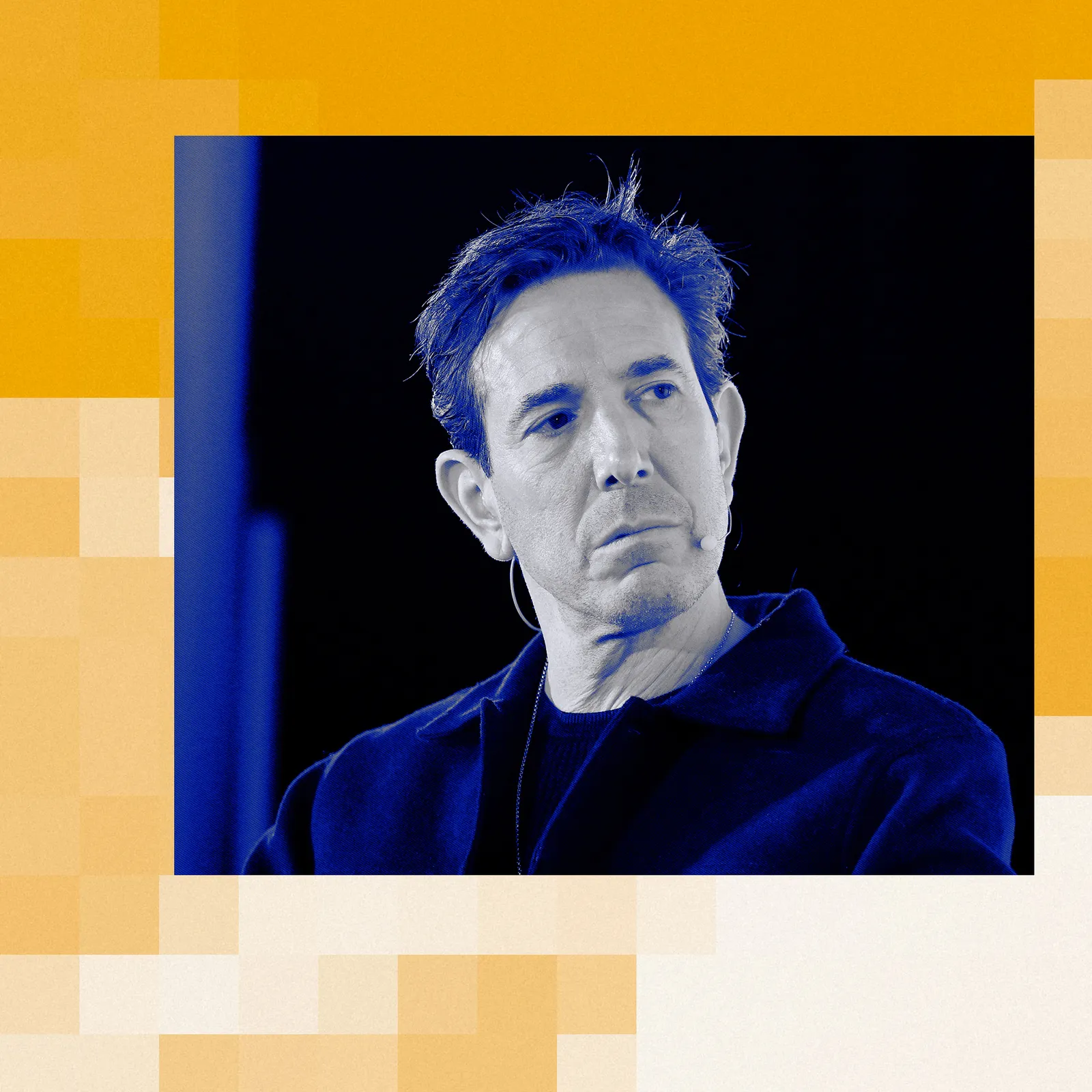

Jeremy Konyndyk, president of the group Refugees International, said he believes Israel allowed the shipments because it wanted to avoid being seen as responsible for a famine finding.

“A formal famine determination would signal a historically grave calamity brought about by the military tactics of the Israeli state,” said Konyndyk, the former director of the US Agency for International Development’s Office of US Foreign Disaster Assistance. “That word – famine – has a lot of power … It takes it from a technical determination to a historical judgment. And that, of course, was not a historical judgment that the Israeli government wanted to be held responsible for.”

COGAT did not respond to questions about whether Israel allowed more aid into Gaza to prevent a famine determination or whether outside pressure influenced Israel to temporarily loosen restrictions.

An IPC famine finding could be used in legal cases against Israel or its officials, some experts say.

In November, the International Criminal Court in The Hague issued arrest warrants for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his former defence chief. One of the war crimes that’s alleged: starvation as a method of warfare. Starvation is also at the crux of South Africa’s case accusing Israel of state-led genocide. That case is before the International Court of Justice, the UN’s highest legal body.

Although a famine finding would not be necessary to prove criminal liability, “it would emphasise the extreme urgency of changing Israel’s behaviour,” said Tom Dannenbaum, associate professor of international law at Tufts University’s Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy.

Some experts observed that a famine determination by the IPC would make little difference in terms of mobilising assistance to Gaza. The issue is whether Israel will “lift restrictions on access and ensure humanitarian organisations can deliver aid safely,” said Alexandra Saieh, head of humanitarian policy and advocacy at Save the Children. The aid group is one of 19 organizations and intergovernmental institutions that oversee the IPC.

As the IPC examines its own criteria, some experts suggest it should broaden its methods and its mindset.

The IPC typically gets much of its information from aid workers who go from household to household to glean key data on acute malnutrition and death rates. In Gaza and other conflict zones, violence and repeated displacements make such surveys difficult. The consequence: Famine can be missed or discovered too late.

The IPC famine thresholds require specific assessments: of mortality, of the percentage of households facing an extreme lack of food and of the percentage of malnourished children. But some food-security experts say the IPC’s standards, part of an evidence-driven system designed to objectively classify acute food insecurity, need to be revised and shouldn’t be the only determinant of famine.

Ainashe, the analyst with relief group CARE, said the IPC should change its approach in besieged areas. The monitor, he said, should accept not just numerical data for some of the thresholds it uses to determine famine. For instance, he said, the IPC could conclude a famine is occurring when at least 20% of households are suffering from extreme hunger – a threshold it currently adheres to – while also using on-the-ground anecdotal information from doctors, families and aid workers indicating that malnutrition and mortality rates are rising fast. The system, Ainashe said, must “err on the side of saving lives.”

The IPC says it has adapted its methods in locations affected by conflict. One example: It uses information gathered through phone surveys in areas data collectors might be unable to visit, said Lopez, the IPC global program manager. But Lopez warned that lowering the bar on data requirements too much “would put the credibility of the IPC at risk and would likely result in weaker action.”

Some experts believe the IPC should explore how to expand its use of satellite imagery and other tools so it could track everything from displacement patterns to crop growth or grave sites, as Reuters did in assessing hunger in Sudan. They also say that the IPC system relies too much on statistics and not enough on in-depth interviews with people living through hunger about how they are surviving and their experiences.

“The IPC approach has lost sight of what famine is in the real world,” said Chris Newton, a former IPC analyst who examined issues related to conflict and food security. He is now a visiting fellow at the Feinstein International Centre at Tufts University in Boston. “Given the risks of mass death, it needs to find better ways to incorporate every potentially useful piece of information available.”

Shay, the pulmonologist who volunteered in October, said he didn’t need more data to understand what is happening in Gaza.

The paediatric ward at Nasser Hospital averaged about 140 patients each day Shay was there, he said; the ward had 40 beds. Children and their mothers slept on mats in the hallways, and the crowded conditions increased the risk of infections spreading. Many children suffered from dehydration, diarrhoea or hepatitis from drinking dirty water. He believes the conditions will only worsen.

“The children are going to be sicker,” Shay said. “More infections will spread.”

According to various methods of measuring hunger that pre-date the IPC system, Gaza is already mired in famine, said Alex de Waal, executive director of the World Peace Foundation at Tufts’ Fletcher School. In a recent essay, de Waal estimated that starvation and related diseases there have claimed at least 10,000 lives. He said his assessment is an approximation, not a tally: He reached the figure by examining a range of death estimates from the territory and reviewing mortality figures in other countries beset by food emergencies similar to those in Gaza.

Just last week, the U.S. government’s own hunger monitor, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), published a report that projected famine by early 2025 in part of northern Gaza. After the report was issued, the U.S. ambassador to Israel, Jack Lew, wrote that it relied on data that “is outdated and inaccurate.” Subsequent to Lew’s critique, FEWS NET withdrew the report, stating that its alert is “under further review” and that it expects to update the report in January.

De Waal decried Lew’s comments and said the situation underscores how the dearth of numeric data demands a reliance “on extrapolation, inference, empirical evidence, logic, and expert judgment.” If the U.S. were concerned about the quality of the data, “it would be straightforward to demand that Israel permit international agencies to operate and collect such data,” de Waal said.

Lew’s spokesperson and the U.S. State Department declined to comment.

As for the debates over the exact toll hunger has taken in Gaza, de Waal said they miss a larger point. “We need to dethrone the concept that if it’s not famine, it’s OK,” he said. “Even if it’s not a famine, it can be truly terrible.”

Children are especially susceptible to malnutrition, and their developing immune systems struggle to stave off potentially deadly infections. The story of one Gazan child who died earlier this year illustrates the peril.

- A Reuters report