Just how fit do you have to be to be a Premier League footballer? It’s a simple question with, it turns out, a not-so-simple answer.

First, ‘fitness’ encompasses a huge range of different factors: strength, endurance, mobility, speed and power. Second, footballers don’t typically do what the rest of us might do in the gym to see where their fitness levels are at. Why? Because their movements are specific to football performance, not gym performance.

What do they do, then, to see how fit and ready they are for, seeing as we’re here in August, a new season? To help answer that question, we enlisted the help of 292 Performance, which provides elite-level support to top footballers and has worked with more than half of the Premier League’s clubs.

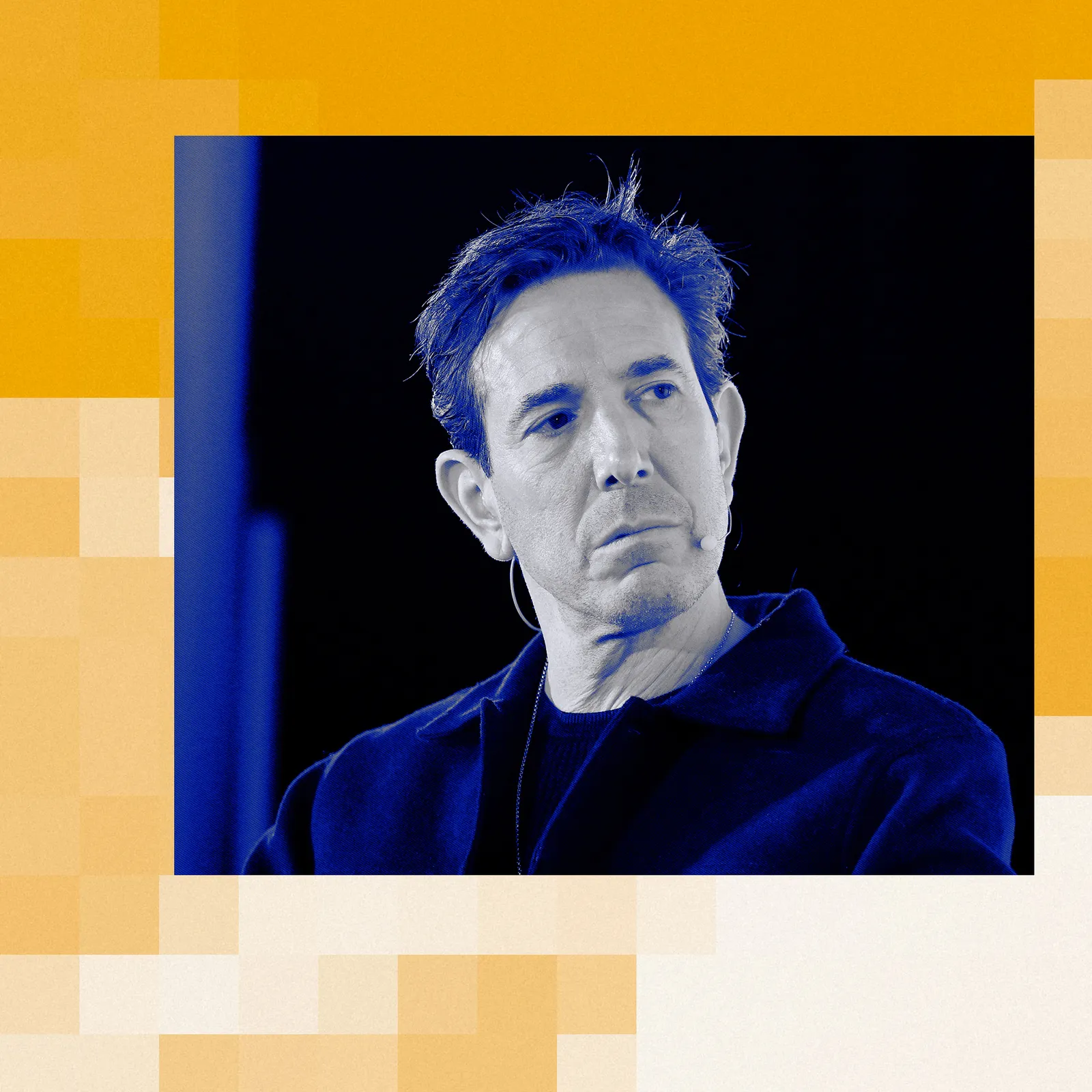

During an afternoon at Pennyhill Park – a luxury spa hotel in the countryside southwest of London, with the bonus of elite sports facilities, which also serves as the primary training base for the England rugby-union team – staff from 292 subjected journalist Eduardo Tansley to a series of tests designed to show how he measures up against the average Premier League footballer: “We’re going to treat you as if you’ve just signed with a professional club,” says the company’s lead physical-performance coach Mathew Banks,

For context, Eduardo, now 24, spent four years at EFL club Lincoln City’s academy as a teenager and still plays regular five-a-side when he is not writing articles, so he is probably in better shape than most of us who watch sport for a living instead of playing it.

Banks explains that the day will start with a movement assessment, before leading Eduardo into the gym and asking him to execute a series of walking lunges that get progressively more challenging. There are straight lunges, lunges with rotations, lunges with rotations and lunges into arabesques (standing on one leg with the other extended behind you), during which Eduardo manages to stay impressively upright. Then it’s on to marches while holding a pole straight overhead.

His every step is observed closely by Banks, who is looking at stability, mobility and lower body control. The drills also double as a warm-up for the testing to come and they’re effective: by the time he’s finished, a few small beads of sweat have formed on Eduardo’s brow.

From there, we move into a small room that houses a pair of metal plates on the floor that look a bit like a digital weighing scale. These are actually VALD (Vertical Assessment of Landing Dynamics) force plates and while they do measure a person’s weight, they also record a lot of detailed information about the amount of power an individual can apply through their legs, how long it takes them to do that and the symmetry of their left side versus their right.

“It is super-sensitive,” says Banks, who connects the plates to an app on an iPad so he can give immediate feedback on Eduardo’s jump efficiency.

He is tested on four different types of jump: a counter-movement (a vertical leap with hands on hips designed to assess an athlete’s explosive strength, neuromuscular efficiency and overall functional capacity), pogos (a series of vertical hops focusing on minimal ground contact) and single-leg variations of both these movements.

The amount of data Banks can glean simply from Eduardo jumping up and down on two metal sheets is staggering.

Jump height is the most obvious. Eduardo’s best effort was 33.70 centimetres (13.3 inches), which is some way below what would be expected from a Premier League footballer. The Premier League average among the players 292 have tested is 39 centimetres. To be in the top five per cent, you would need to jump above 48 centimetres (almost 19 inches).

While jump height is correlated with the concentric part of the jump (the way up), information can also be taken from the eccentric part (the way down).

Here, Banks is examining reactive strength: how quickly Eduardo can apply force into the platform and what he gets in return. The score given to the athlete is the outcome of their jump height divided by time to take off. Eduardo’s score is 0.51 here, with the average for a Premier League player coming in at 0.70.

“This is a really important metric for change of direction and acceleration,” explains Banks. “You’d normally associate guys who are really fast with pretty good jump heights or reactive strength.”

Banks is also looking at eccentric breaking force here, which is the amount of force Eduardo is applying as he comes down from a jump; a fundamental skill that allows athletes to quickly change direction, absorb impacts and prepare for the next movement. Here, he notes that Eduardo applies significantly more force on his left side compared to his right – a red flag when it comes to assessing an athlete’s injury-risk profile and something Banks says 292 Performance would look to address quickly through the athlete’s training programme.

Then it’s on to the hopping test.

With hands on hips, Eduardo is instructed to do 10 jumps while keeping contact time with the plates to a minimum, while still getting as much height as possible. Only the top five jumps in the set are used to calculate the athlete’s overall score. In this case, the ‘score’ is an athlete’s reactive strength index (RSI), which is a combination of how much force they apply and how quickly they do it. “If you can’t apply the force as fast, then it’s not as useful as it could be in a sporting setting,” Banks says.

Eduardo’s mean contact time is good (179 milliseconds – the average for a Premier League player is 0.17s) but his jump height is not at 15.40cm, which means he gets an RSI score of 1.98, whereas elite-level athletes are expected to score around 3.0 to 3.5. The key to improvement here, says Banks, would be finding how Eduardo can apply more force to drive more height into those hops.

The last bit of testing indoors is done on a piece of kit called a VALD force frame, which again connects straight to Banks’ iPad.

Although the focus here is on strength, there are no weights to be seen. This is all about isometric strength – contracting a muscle and holding that without movement. This kind of test makes it easier to isolate and identify strengths and weaknesses in a particular muscle than with a compound movement such as a squat, which can mask imbalances and inefficiencies because it requires multiple muscles working together.

Another plus to this type of testing is that it has less impact on the player, Banks says: “It doesn’t cause as much delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) and it’s only a few seconds of effort.” All of which means the exercise can be repeated more frequently throughout the season to assess how an individual’s training plan is working.

The force frame works by pressing into the pads or sensors with various parts of the body for a count of five (while Banks shouts “PUSH! PUSH! PUSH!” into your ear), resting briefly and then doing the same again twice more. Banks tests Eduardo’s hamstring, calf, hip and groin strength using the machine and is looking not only at strength but the symmetry between the left and right sides of his lower body and the ratio of hip versus groin strength.

“It’s quite common for footballers to have really strong groins and really weak hips because of the nature of the sport and how much they use their groins,” says Banks. “Hernias are quite common because of that. Everything they will do is high-velocity winding; turning inside, which involves internal rotation of the thigh.”

- A Tell Media report / Adapted from The Athletic