A BBC investigation into hotels housing asylum seekers in the UK revealed “evidence of black market work.” This might evoke imagery of illicit dealings that will only fuel right-wingers’ racist and xenophobic demonstrations.

But in reality, this shows people simply eking out a living – often as low-paid labourers such as food delivery drivers, whose work we considered essential, and even clapped for, during the Covid-19 pandemic. If anything, it is evidence of a deeply broken system where asylum seekers are compelled to work in secret just to get by – but also of people’s desire to make themselves useful even in the direst conditions.

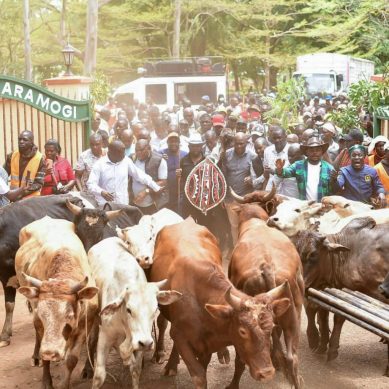

I witnessed the same thing in my research on how economies emerge and grow in refugee camps, conducted in Kakuma in Kenya. People in search of safety – from war, persecution, disaster or hunger – end up in camps with inadequate services and poor opportunities.

Formally, they are not allowed to work, set up a business or own property – and yet these “black markets” appear.

I saw scores of stores offering goods and services, including ones people might not expect, given how camps are often portrayed in the media: beauty salons, photography studios, bridal gown rentals and even cinemas. I met refugee farmers who covertly traded parcels of arid land with which they managed to miraculously grow vegetables. I sat in makeshift offices where people spent their day in front of a laptop (powered by informal energy suppliers) trying to earn some money as digital freelancers.

All this is technically not allowed. But it is commonplace in refugee camps and asylum centres globally – from Kutupalong to Calais. These black markets exist mostly because people cannot meet their needs otherwise. In the UK, those staying in the hotels are expected to subsist on £9.90 a week, or about $13. During my time in Kakuma, the UN’s cash assistance – called bamba chakula – was around £9 per person per month. So, people resort to taking on clandestine jobs or even selling the in-kind goods they receive so they can have the money for their priorities.

This tells us two things: that humans resist a life of destitution imposed upon them; and that refugees can positively contribute to society if we allow them to.

Many have framed refugees’ and asylum seekers’ economic activities as resilience. I disagree. This is their active resistance – against forces that oppress them.

That our fellow human beings find a way to survive in adversity should not be surprising. There are other examples in history, where markets emerged out of hardship and despite suppression, such as in former totalitarian regimes where clandestine economic activities preceded – and even spurred – economic reforms. But equally remarkable is people’s pursuit of agency, meaning and community even in these prison-like conditions – both through the markets (for instance, the hotel residents’ preference to buy and cook food they actually like; or the leisure micro-industry in Kakuma), and outside of them (through gifts and reciprocity within a moral economy – like how, in the BBC piece, a security guard made a running track for children; or in the formation of community-based organisations and cooperatives where refugees in camps can support in each other).

The existence of black markets shows that refugees and asylum seekers have something positive to contribute – but only if we let them. In the UK, immigration, including from refugees, grows our economy – contrary to far-right claims (such as Schroedinger’s immigrant, who simultaneously scrounges off benefits and steals jobs!).

Analysis by the Migration Observatory at Oxford University shows “higher net migration leads to lower deficits and debt, because migrants tend to be of working age”. Even the previous Conservative government announced that refugees “are contributing nearly £1 million each year in income tax and national insurance”.

In Kakuma, these black markets have grown over time into a bustling economy – one that even locals have come to depend on for their own livelihoods. In a 2018 study by the International Finance Corporation, the fused economy of Kakuma Camp and town generated $56.2 million worth of consumption.

A World Bank study found that for Kenyan locals, proximity to the refugee camp is associated with better economic and social indicators. But we should not romanticise the grit of people in desperate situations. Their lack of rights and protection means they are often exploited for profit. Many have framed refugees’ and asylum seekers’ economic activities as resilience.

I disagree. This is their active resistance – against forces that oppress them. If those of us who are privileged with safety or won the lottery of citizenship were in their shoes, I’m certain we would truck, barter, and exchange just the same.

The appropriate response, therefore, is not cruel raids or hateful marches, but a change in how countries – like Kenya or the UK – welcome and guarantee the welfare of those who dare to seek refuge.

- A Tell Media