Becoming a man in Tiriki: Cultural fanfare as Luhyia subtribe embarks on circumcision – a sacred rite of passage

From the misty hills of Hamisi, the haunting timbre and ancient chants once again reverberate across the valleys of Vihiga as the Luhyia sub-tribe, Tiriki, ushers in the revered circumcision season – a deeply cultural and spiritual rite of passage that marks the transition of boys to manhood.

The ceremony, held every five years, officially began this month on July 21, drawing in families, elders and entire villages in a tradition that remains one of Kenya’s most elaborate and respected cultural practices.

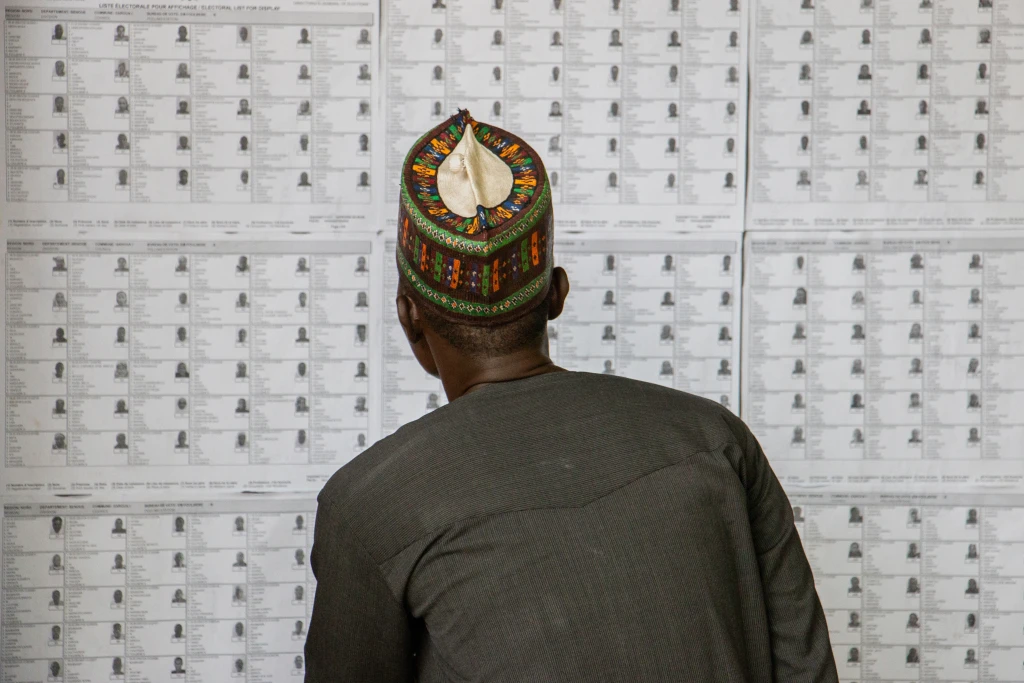

In the weeks leading up to the circumcision, selected boys – aged between 12 and 15 – are ceremoniously shaved and withdrawn from their families and normal routines to undergo training.

They visit relatives for blessings and receive lessons and counselling from older men on the fundamentals of adulthood. Mothers prepare traditional meals while fathers and uncles coordinate sacrifices and rituals steeped in ancestral symbolism.

The ceremony is synonymous with feasting.

“I have waited for this moment since my son was born,” said Jane Mmbone, a mother from Shiru village. “It’s not easy, but it’s an honour. It means he will now be respected as a man.”

On the eve of circumcision, the candidates walk without clothes – but wear wildlife skins – accompanied by singing villagers. Men who accompany them wear wildlife skins too. The wildlife skins are a symbol of fearlessness – a mark of valour and ruthlessness.

Ordinarily, the wildlife skins favoured are leopards and colobus monkey skins. A leopard bears totemic significance in Luhyia culture. A colobus monkey is a symbol of grace.

“That sound of timber gives me butterflies in the belly,” said Brian Muyeka, a 19-year-old who underwent the ritual in 2020. “It reminds me that something big was about to happen. It made me proud – it felt like walking into history.”

The actual circumcision takes place at dawn in a sacred at a restricted venue. Only initiated men and elders are allowed to witness the procedure, performed by a professional circumciser – mushefi / mukhevi / mukevi/ mushevi – chosen by the council of elders. Women and uncircumcised individuals are prohibited from accessing the venue.

“That moment separates boys from men,” noted Allan Akasi, a youth leader in the region. “You can’t fake courage there. Everyone will remember how you handled it.”

Fear is scorned at and it becomes a tag one lives with all their life. In some cases it stigmatises entire families of the boys who show fear during the cut. The procedure takes less than a minute.

Following the operation, the boys are taken to a forest for isolation huts known as irumbi (isolation to ‘ward’) where they spend close to a month in seclusion. During this period, they taught male hygiene, cultural pride, discipline and responsibility – virtues expected of a Tiriki man.

They are also given new names, marking the death of their childhood and the birth of a new identity.

As they begin to heal, the initiates return to the village daily, dancing in elaborate garments made from animal hides, sisal, and beads. Their dances and songs – fierce and spiritual – remind the community of the power of culture and the discipline instilled by tradition.

“Every evening, I leave my work to watch them dance,” said Rose Lumbasi, a trader at Musasa Market. “It reminds us all that culture is still alive. It’s beautiful and emotional.”

Later in the process, each initiate is allowed a brief, supervised visit home – under strict silence. They are not allowed to speak to their mothers. Their meals are taken quietly in banana plantations under the watchful eyes of male custodians, reinforcing the symbolic severing of childhood.

The final ceremony brings jubilation and closure. Clad in traditional regalia – leopard and colobus monkey skins – the initiates are given final instructions, clan names and words of wisdom before they are formally released to their families “as men”.

“That day changed my life forever,” added Brian Muyeka. “It’s the day I truly felt I belonged. Not just as someone’s child, but as a man of my people.”

As the ceremonies get underway around Tiriki villages this season, the youth are equipped with what is considered ‘inalienable’ cultural rights: that this tradition, deeply rooted in identity and unity, is far from fading. It remains a living, breathing testament to the resilience of African culture.

Selected boys aged between 12-15 before circumcision and after circumcision in their traditional regalia.

- A Tell Media / KNA report / By Ian Mugamangi