A group of white descendants of Dutch settlers to South Africa landed at Washington Dulles International Airport last week, part of a new Trump administration programme aimed at “Afrikaners in South Africa who are victims of unjust racial discrimination.”

The group, Trump officials claimed, were fleeing “white genocide.”

On social media, South Africans turned the departure into a joke, dubbing it the Great Tsek, in a double entendre referencing both the Great Trek – the historic migration of Dutch settlers from the Cape Colony into the interior of the country in the mid-1800s – and the word tsek, an Afrikaans colloquialism that crudely translates to “fuck off.”

The departure was the latest development in a saga that has shocked, worried and amused South Africans, in equal measure.

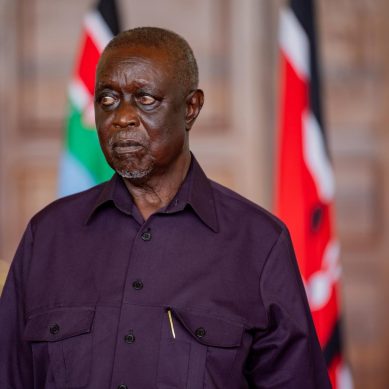

The events that led to that flight, and indeed to the executive order that enabled the flight, began during President Donald Trump’s first term in May 2018. Kallie Kriel, the CEO of an Afrikaner rights movement called AfriForum, and his deputy Ernst Roets, travelled to America to make the case to US officials and diplomats that South Africa’s Afrikaner farmers were being racially targeted and would be harmed by a proposed law that would expropriate land from owners who had not used it.

In Washington DC, the men met with then-national security adviser John Bolton and staffers in Senator Ted Cruz’s office. Roets also secured an interview on Fox News. Tucker Carlson interviewed him about his book, Kill the Boer, which the duo were using as a calling card on their trip. In it, Roets argues that since the end of apartheid, South African authorities have done little to protect white victims of farm murders.

Carlson caught Trump’s attention a few months later when he ran a follow-up segment on “white farm murders” in which the anchor insisted that the government of South Africa was “taking land from white people on the basis of their skin colour.”

In response, Trump tweeted, “I have asked Secretary of State @SecPompeo to closely study the South Africa land and farm seizures and expropriations and the large scale killing of farmers.”

Kriel’s lobbying trip had been hugely successful, but while he was interested in making global links, the Afrikaner’s main focus was domestic South African politics. He knew the attention the visit had garnered would irritate the African National Congress government, which has been eager to safeguard its international reputation for peace, stability and racial harmony since it was first elected into power in 1994.

America was just a handy backdrop: For AfriForum, the real prize was increasing its reach and influence back home in South Africa, where Afrikaners have played a significant role in national affairs since the arrival of the first Dutchman at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652.

During the apartheid era, Afrikaners largely saw themselves as a self-sufficient white tribe of Africa. Their leaders were insular and distrusted global political institutions. After all, the Afrikaner nationalist rulers were reviled by the international community, which sanctioned their government and declared apartheid a crime against humanity.

When apartheid was defeated by a negotiated settlement between the Afrikaner government and Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress party following years of international and domestic pressure, Afrikaners were promised that they could keep their land, assets and businesses, if they pledged to integrate into the wider society and respect a new Constitution that their leaders had helped to draft.

At the level of political representation, the National Party, which had implemented apartheid and ruled the nation since 1948, collapsed after the first democratic elections. It folded into the Democratic Alliance a few years later, which, broadly speaking, represented white South Africans of both British and Afrikaner heritage.

Many white people of course voted for the ANC and other political parties, but voting patterns show a clear preference amongst white people for the DA.

The Afrikaner community’s economic muscle has remained largely in place as its political strength has waned but a cohort of organisations have emerged to present the acceptable face of white nationalist ideology: white victimhood.

A cohort of organisations have emerged to present the acceptable face of white nationalist ideology: white victimhood.

The largely white trade union Solidarity and its policy arm AfriForum have been able to assert this victimhood in response to the emergence of the Economic Freedom Fighters, a political party led by firebrand Julius Malema, who is popular with the country’s youth.

The EFF and AfriForum were engaged in a long-running court battle over the EFF’s use of the Xhosa-language song Dubul Ibhunu, which loosely translates as Kill the Boer. The song was popular in the 1970s and 1980s as a chant by freedom fighters seeking to overthrow white minority rule. In court, AfriForum argued the song made Afrikaners feel unsafe. S

South Africa’s Constitutional Court ruled that given its history, those singing Dubul’ Ibhunu were protected “under the rubric of freedom of speech.” For the last decade, as the court case wore on and AfriForum found its voice in America, Kriel became a familiar face in the South African media landscape.

Unlike the dour Afrikaner leaders of the past who shied away from speaking English, Kriel is affable, comfortable speaking English, and a constant media presence who can debate smoothly. But his beliefs are still linked to his predecessors. He is on the record as stating that when Dutch settlers moved into the interior of the country in the 19th century, there were no inhabitants. Likewise, Roets comes across as an even-tempered policy wonk, a demeanour he put to use this week when he appeared on “The Charlie Kirk Show.”

After their flash of success catching the eye of the first Trump administration, AfriForum shifted their focus back to domestic politics after the unsympathetic Joe Biden came into the White House, building a litigation unit to fight for Afrikaner rights and campaigning against the slow-moving land bill.

Then Trump returned. Within weeks, he issued his executive order, “Addressing Egregious Actions of The Republic of South Africa.” South Africans, including those in AfriForum and Solidarity who had fed Trump the white genocide conspiracy in the first place, were plainly shocked.

- A Tell report / Republished from The Intercept