Although populism has become a focus of scholarly interest in the past decade, there has been much less research on how militaries worldwide have reacted to the rise of populist leaders (Yilmaz and Saleem, 2021).

In this article I want to focus on the interaction between military populism and generational populism in Uganda by taking President Tibuhaburwa Museveni as the military populist and Kyagulanyi Ssentamu alias Bobi Wine as the generational populist. I will demonstrate that military populism and generational populism was played out in the recently concluded by-election in North Kawempe constituency.

Populism encourages the centralisation of power as it exalts one person and extols one leader. Dissent and diversity are downplayed and ignored. The military, as an institution, is based on strict hierarchy and the criminalisation of dissent within is closer to populist politics than constitutional politics. The anti-intellectualism and xenophobic rhetoric of populists are often also closer to the military’s thinking. The military – save for the most senior ranks – can also be anti-elite.

Military officers, especially in lower ranks, may identify more with ordinary people than the ruling elite. Populists and the military may also agree on the importance of “getting the job done” instead of following legal or constitutional processes, which may cause delays (Yilmaz and Saleem, 2021).

There is growing belief that military populism is the primary threat to democracy in Africa. Military populism is becoming the new norm in Africa in general (Usman, 2024) and Uganda in particular. Increasing involvement of the military in the politics of several African countries is driven by the approval of ordinary masses who perceive them as saviours from corrupt, incapable and incompetent civilian alternatives. The more successful coups there are in Africa, the more likely future coups become (Usman, 2024).

Hakki Taş observes that populist centralisation of power occurs when the military captures power, fosters control over the armed forces and exacts a lot of impact on civilian oversight, depressing political literacy and political development of its civilian victims.

In Uganda, the military has been the norm since 1986 with the gun at its centre and President Tibuhaburwa Museveni as the perennial populist military ruler. Initially the military populist government preferred decentralisation of of power and authority, which gained a lot of public support. However, with the passage of time, the populist government recentralised power and authority in its perennial populist ruler.

This meant that the many local districts it created would have no power and authority over how the taxes they collected were allocated and by how much. They have to send the tax collections to the centre, which had the power and authority over the money and how to spend it. As we have seen, over time, social services have been devalued and more most of the money is being spent on central administration, politics, the military, the president, the State House, regional wars and controlling the movements and actions of civilians and political parties.

Military populist leaders in Uganda spend a lot of time, energy and money building individual loyalty. They do not hesitate to pay their loyalists excessively highly compared to non-loyalists of similar qualifications and experience. Sometimes the loyalists need not have the required qualifications and experience. The Public Service Commission and other statutory bodies need not be primarily involved in their appointment.

Hakki Taş points out that populist military rulers are particularly after building community loyalty and ideological loyalty. This tends to sway their minds away from developing and transforming the countries they lead to building personalist power.

Uganda, community loyalty and ideological loyalty are being built through ideas such Saccos and programmes such as Bonna Baggagawale, Myooga, Operation Wealth Creation and Parish Development Model and also the so-called National Ideological School at Kyankwanzi.

Unfortunately, these are prone to corruption and are impoverishing communities since they target individuals, not whole communities. However, they are the ones the populist military ruler routinely uses to access the impoverished communities at the expense of other alternative leaders who are excluded militarily from the population. Apparently, as Hakki Taş has pointed out populist leaders can embody both militarist and anti-militarist traits. Besides, increasing support for populist leaders grants them the capacity to either suppress, negotiate with or deploy armed forces as needed.

In Uganda, this frequently happens during elections during which the populist leader seeks to show the absolute majority of Ugandans support him. He wants to perennially prove that all councils and the Ugandan parliament are solidly his as loosing the support base to Opposition would undermine his populist stance. Unfortunately, the military populist leader is undermining democracy instead. Enhancing his military populism and personalist power in enhancing democratic backsliding in Uganda.

Let me now turn to the generational populism of Kyagulanyi Sssentamu aka Bobi Wine, which has been written about by Luke Melchiorre (2023) in his article, ‘Generational Populism and the Political Rise of Robert Kyagulanyi aka Bobi Wine in Uganda’.

The article analyses the political rise of the Ugandan opposition leader, Robert Kyagulanyi, aka Bobi Wine, arguing that he has a deployed a novel type of generational populism – a mobilising political discourse, which frames the struggle between ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’ in generational terms, defining the former in relation to their status as youth and in antagonistic opposition to an elite, which is depicted as defending a gerontocratic political order.

At a theoretical level, the article broadens political science’s conception of populism, by introducing a new subtype of the political phenomenon, which demonstrates the importance of intergenerational dynamics in the construction of the discursive categories of ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’. While it argues that Kyagulanyi’s success demonstrates the potential of populism in African countries to electorally challenge incumbent regimes, by helping to build political coalitions across ethno-regional lines, incorporating previously excluded social groups into the political process, it concludes by stressing that Kyagulanyi’s political project has failed to offer any real ideological alternative to the neoliberal orthodoxy that has characterised President Tibuhaburwa Museveni’s Uganda over the last four decades.

Apparently, soon after the 2021 presidential and parliamentary elections, President Tibuhaburwa Museveni dismissed Kyagulanyi as “being backed by foreigners and homosexuals” and as a populist without an agenda (Luke Melchiorre, 2021).

However, soon after President Trump came to power and froze foreign to Africa, it became clear that Uganda had been receiving billions of dollars through the World Bank and USAID to fund homosexual-related activities with the knowledge of President Tibuhaburwa Museveni’s government.

President Tibuhaburwa Museveni’s military populism and Kyagulanyi’s generational populism are set to clash again during the 2026 general election. A preamble of what is likely to happen in 2026 elections, it played out on March 13, 2025 in the North Kawempe parliamentary by-election.

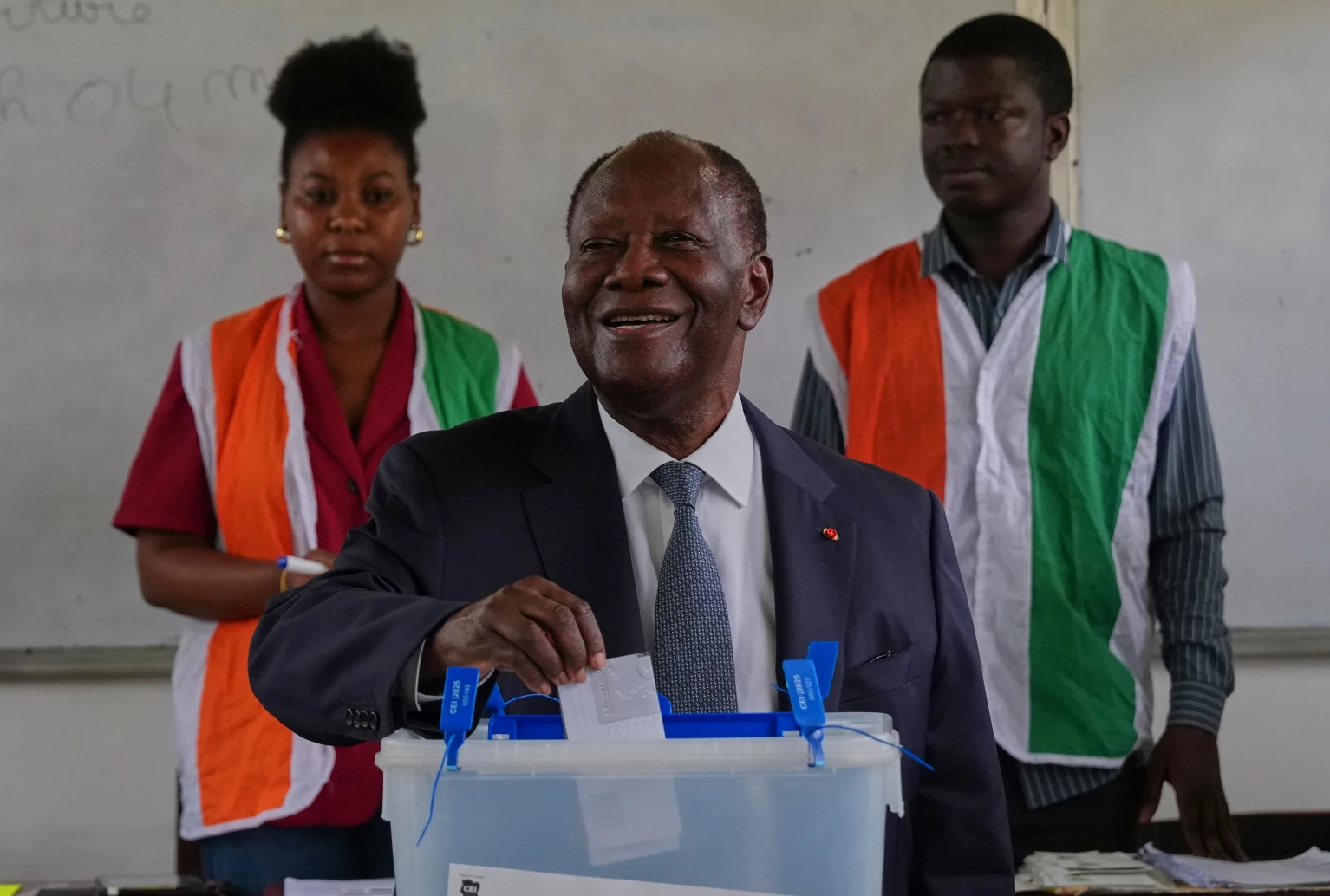

It took the Independent Electoral Commission 11 days to confirm National Unity Platform’s Elias Luyimbazi Nalukoola’s victory against National Resistance Movement’s Faridah Nambi. The Uganda Gazette Notice gives Nalukoola 175 more votes than the 17,764 he originally got and Faridah Nambi’s original 8,593 rises to 9058. Nalukoola said his victory was against brutality. Indeed, the by-election was highly militarised by the Uganda police, Uganda Peoples Defence Forces and the Joint Anti-Terrorism Task Force (JATT). It was as if the by-election was a matter of life and death. There was a lot of violence against journalists.

President Tibuhaburwa claimed NRM votes were stolen by NUP despite heavy deployment. He claimed those who committed violence were NUP members and threatened that NRM would go to court. However, many NRM members, including Ofwono Opondo, the government spokesman concurred that Nalukoola won the contest despite state violence.

Ofwono Opondo describes the NRM’s performance as “an exercise in futility” and accused the party of losing touch with the “broad base of ordinary supporters, voters and common sense.” He added, “One wonders why the party mounted this by-election – for a seat lasting only seven months before the general election – into a high-stakes, do-or-die affair.”

One thing is true. Neither military populism nor generational populism add much value to democratic development. Democratic development refers to the process of strengthening and expanding democratic institutions, practices and values within a society, aiming to achieve a more just, equitable and participatory form of governance. Throughout President Tibuhaburwa Museveni’s military populism democratic institutions have been eroded, political pluralism has been weakened and country cannot boast that it has built democratic practices and values and that there is meaningful participation by the people in the leadership and governance of the country. Military populism amidst neoliberalism is confusing democratisation in Uganda.

It is a challenge to liberal democracy (Galston, 2018). It is unlikely that either military populists or generational populists are influencing the development of democratic attitudes at the citizen level (Zaslove and Meijers, 2023). In Uganda many who support the military populist are driven by either goods, jobs or money they receive from him, not hope for democracy with him at the helm.

However, those who support the generational populist are heard saying, among other things, that they want democracy, freedom, justice and equity and tjat they are tired of brutality, abuse of human rights and exclusion of their lot from the opportunity to lead and govern their country towards meaningful independence, sovereignty and citizenship. Lastly while the military populists are committed to the politics of interests, the generational populists are committed to the politics of identity and belonging.

For God and my country

- A Tell report / By Oweyegha-Afunaduula / Environmental Historian and Conservationist Centre for Critical Thinking and Alternative Analysis (CCTAA), Seeta, Mukono, Uganda.

About the Centre for Critical Thinking and Alternative Analysis (CCTAA)

The CCTAA was innovated by Hyuha Mukwanason, Oweyegha-Afunaduula and Mahir Balunywa in 2019 to the rising decline in the capacity of graduates in Uganda and beyond to engage in critical thinking and reason coherently besides excellence in academics and academic production. The three scholars were convinced that after academic achievement the world outside the ivory tower needed graduates that can think critically and reason coherently towards making society and the environment better for human gratification. They reasoned between themselves and reached the conclusion that disciplinary education did not only narrow the thinking and reasoning of those exposed to it but restricted the opportunity to excel in critical thinking and reasoning, which are the ultimate aim of education. They were dismayed by the truism that the products of disciplinary education find it difficult to tick outside the boundaries of their disciplines; that when they provide solutions to problems that do not recognise the artificial boundaries between knowledges, their solutions become the new problems. They decided that the answer was a new and different medium of learning and innovating, which they characterised as “The Centre for Critical Thinking and Alternative Analysis” (CCTAA).

Further reading

Abubaker Usman (2024). Military Populism is the Primary Threat to Democracy in Africa, LSE, February 14 2024. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/africaatlse/2024/02/14/military-populism-is-the-primary-threat-to-democracy-in-africa/ Visited on several security operatives, including 25 March 2025 at 10:56 am EAT

Franlin Draku (2025). Kawempe North By-Election: EC Finally Confirms Nalukoola’s Victory. Daily Monitor, March 24 2025, https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/news/national/kawempe-north-by-election-ec-finally-confirms-nalukoola-s-victory-4977476 Visited on 25 March 2025,

George Asiimwe (2025). Opondo Rebukes NRM Over Kawempe Election Debacle: Stop Violence, Deliver Public Services. ChimpReports, March 23, 2025. https://chimpreports.com/opondo-rebukes-nrm-over-kawempe-election-debacle-stop-violence-deliver-public-services/ Visited on 25 March 2025 at 13:13 pm EAT.

Hakkı Taş (?). Marching to the Populist Drum? The Militaries role in populist governance. THE LOOP, https://theloop.ecpr.eu/marching-to-the-populist-drum-the-militarys-role-in-populist-governance/ Visited on 25 March 2025 at 11:11 am EAT.

Ihsan Yilmaz and Raja M. Ali Saleem (2021). Military and Populism: An Introduction. European Center for Populism Studies, April 26 2021. https://www.populismstudies.org/military-and-populism-an-introduction/ Visited on 25 March 2025 at 10:36 am EAT.

Luke Melchiorre (2021). The Generational Populism of Bobi Wine. ROAPE, February 12 2021, https://roape.net/2021/02/12/the-generational-populism-of-bobi-wine/ Visited on 25 March 2025 at 12:12 pm EAT.

Luke Melchiorre (2023). Generational Populism and the Political Rise of Robert Kyagulanyi aka Bobi Wine in Uganda. Review of African Political Economy Volume 50, 2023 – Issue 176: Pages 212-233 | Published online: 22 Aug 2023.

William A. Galston (2018). The Populist challenge to Liberal democracy. Brookings, April 17 2018 https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-populist-challenge-to-liberal-democracy/ Visited on 25 March 2025 at 13:37 pm EAT.

Zaslove, A. and Meijers, M. (2023). Populist Democrats? Unpacking the Relationship Between Populist and Democratic Attitudes at the Citizen Level. Political Studies, 72(3), 1133-1159. https://doi.org/10.1177/00323217231173800 (Original work published 2024)