Amanda Staveley, the British business executive, is the thread that linked the arrivals of Abu Dhabi and Saudi Arabia’s millions into the Premier League. After helping to broker the sale of Manchester City to Sheikh Mansour in 2008, she was part of the consortium, headed by Saudi’s PIF, that ushered in a new era for Newcastle United 13 years later.

The two deals, though, were very different. Although the Premier League had been comfortable enough giving the greenlight to City being bought by Abu Dhabi United Group, a private equity firm owned by Sheikh Mansour, it was much less welcoming to Saudi Arabia.

Only when “legally binding assurances that the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia will not control Newcastle United” were given did the Premier League finally approve PIF buying an initial 80 per cent stake in the club, triggering wild celebrations outside of St James’ Park.

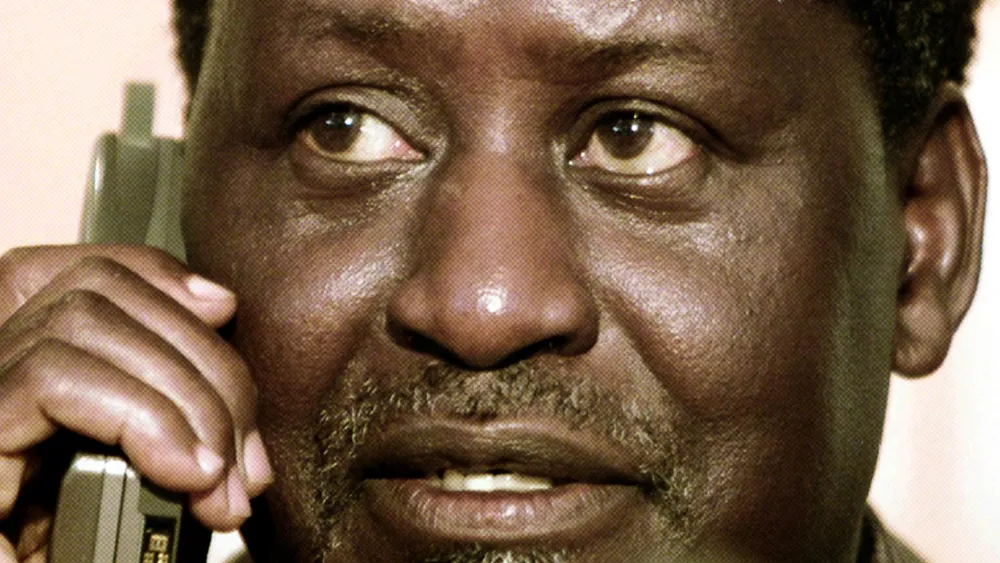

That PIF, the country’s sovereign wealth fund, is chaired by Saudi Arabian Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman (MBS), the Gulf nation’s de facto ruler, soon appeared to count for little once a long-running piracy case, in which Saudi broadcaster beoutQ was alleged to have illegally streamed footage from the Qatari firm and Premier League partner beIN Sport, was resolved.

English football, too, has responded very differently to the arrivals of Abu Dhabi and Saudi Arabia. The first was the unknown, the second – for some, at least – was the unpalatable.

The intervening years had heightened misgivings over the growing involvement of Gulf states in football, with a thousand headlines written about human rights abuses in the run up to Qatar hosting the 2022 World Cup.

Saudi Arabia already had their eyes on landing the 2034 World Cup but this was a country with deeper stains that stretched beyond its poor human rights record and oppression of the LGBT community. Jamal Khashoggi, a journalist critical of the regime, had been murdered inside the Saudi embassy in Istanbul just two years before moves were made for Newcastle, with the CIA later concluding the killing had been ordered by MBS.

Amnesty International, among others, vocally opposed the PIF’s takeover of Newcastle and urged the Premier League to re-examine those assurances given last year after the club’s chairman, Yasir al-Rumayyan, was described as a “sitting minister of the Saudi government” in a US court.

Another sobering report was delivered by Human Rights Watch this week, who said PIF had facilitated and benefitted from human rights abuses. “(MBS) has used the Saudi sovereign wealth fund’s economic power to commit serious human rights violations and whitewash the reputational harm from these abuses,” said Joey Shea, Saudi Arabia researcher at Human Rights Watch.

Not that any of the objections make a difference. Saudi are in the Premier League building now and showing little sign of moving on, even if Newcastle have the feel of a less significant component in the Saudi machine.

Next month, Saudi Arabia will be confirmed as hosts for the 2034 men’s World Cup and huge investment has lured previous Ballon d’Or winners Cristiano Ronaldo and Karim Benzema to the Saudi Pro League.

The wish is for Saudi to become a tourist destination, hosting elite events such as boxing, golf and esports. It all forms part of Saudi Vision 2030, a government programme designed by MBS to diversify the economy before natural resources – and the world’s dependency on them – expire. A thriving entertainment sector to suit the needs of its young population is also high on the agenda.

Newcastle, in the northeast of England, do not have an obvious place in those domestic plans but, having already reached the Champions League once, it has the look of a sound investment.

“If we take Newcastle United as an example, this is just great value for money,” says Chadwick. “You buy Newcastle for £300 million and what you’re buying is 24/7, 365-day exposure around the world.

“But what the Premier League enables is legitimacy and diplomacy. Let’s say you or I want to meet a UK government minister, it might take a while.

“If you own a football club, there’s a fast-track diplomacy that operates within football. It’s a form of diplomacy but there’s also a kudos and status that confers upon you a similar quality and characteristic. What financial value can you put on that? That £300 million is nothing to have that kind of legitimacy.”

If Saudi’s introduction to the Premier League points tentatively towards a pattern that began with Abu Dhabi and Manchester City, the door is open for further investment from the Gulf states.

Qatari money was offered for Manchester United last year as a bid fronted by Sheikh Jassim bin Hamad al Thani proposed a full takeover before Sir Jim Ratcliffe and his petrochemicals firm INEOS settled on a 27 per cent stake last year, while noises have long linked investors from Dubai, another UAE state, with Liverpool.

The Premier League has come to mirror the UK; open to the world for business and with assets for sale.

“Qatar is a really interesting one,” says Chadwick. “I speculate that we could see Qatar in the Premier League at some stage of the next five years… Maybe, just maybe, one of the London clubs would be attractive.

“The other one to look out for is Kuwait. The biggest sovereign wealth fund in the world is Norway but number two is Kuwait. Bigger than PIF, Abu Dhabi, Bahrain. We’re now hearing the first noises of Kuwait thinking maybe they should have some of that.”

Manchester United

The bigger question, of course, is whether the Premier League should have left itself open to the possibility of state ownership. And how different is Gulf money to that flooding in from private equity companies based in the US?

“I get worried as a football fan about states using our football clubs for other purposes and for other goals beyond what fans and communities want them to be for,” says Cockburn.

“It raises the bar for the amount of finances you need in football. States can underwrite their own risk. I don’t want our football clubs to become tools for foreign policy. That’s the risk.”

McGeehan concurs. “We should be deeply and profoundly concerned about state ownerships,” he says. “Everything is geared towards their political power and financial enrichment. It’s not a zero sum game, it comes at the cost of something.

“They could be the anchors that lead to the ultimate downfall of English football because they’re not interested in it as a competitive entity. They’re not interested in clubs as community and social institutions, they’re interested in them as levers for their own political power. That can only be damaging to the game.”

Whatever happens, money from the Gulf has ensured the Premier League will never be the same again.

- The Athletic report